THE UTOPIAN

SPECIAL ISSUE: A Discussion of the Black Lives Matter Movement

- A Raging Fire in the United States: Statement

- Raining on the Parade: Thoughts on the Black Lives Matter Movement (Part 1)

- Raining on the Parade: Thoughts on the Black Lives Matter Movement (Part 2)

- Fight for Our Vision! Against Liberal Cheerleading

- The Politics of Riots

- BLM Helped Shaped 2020 Election—Now Has Its Eyes on Georgia

Statement, June 2020

A Raging Fire in the United States

Written by Wayne Price

Adopted as a Statement by the Utopian Tendency

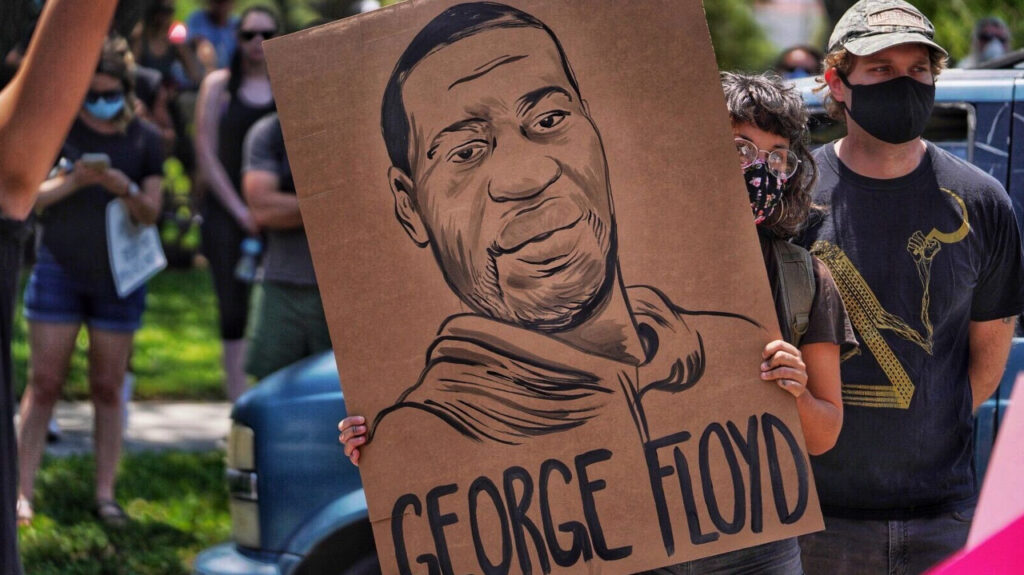

The explosion of rage and sorrow across the cities and towns of the United States is about more than the police murder of George Floyd. It is about the series of Black and Brown people murdered by cops recently and going back to the days of slavery. It is about men and women assaulted by armed police or vigilantes as they sat in their homes, walked or jogged on the street, drove their cars, birdwatched, stood in their building’s vestibule, shopped, or hung around at a street corner. It is both about completely innocent and respectable citizens or people who had committed very minor “crimes” (George Floyd was accused of buying cigarettes with a counterfeit bill) for which they got the death penalty. It is about millions of young men in prison for often trivial offenses such as the ownership of marijuana.

But it was about more than the usual mistreatment by the police, including murder. It was about the whole oppression of African-American people and other people of color. It is now decades after the end of Jim Crow, of racial segregation, which had been enforced by the police and by the extra-legal terror of the Klan. Yet the underlying racism–the knee on the neck–never ended, and the racists in power have renewed attacks on Black people, such as their right to vote (voter suppression).

The terrible pandemic has fallen heavily on Black people, causing many more infections and deaths than in the general (white) population—due to greater poverty and rates of ill-health, plus less available health care. This is true of other people of color. Native Americans have suffered badly; the Navajo Nation has been especially hard hit.

An economic recession (or depression) has been triggered by the pandemic and the methods used to counter it, such as the shutdown of much of the economy. The unemployment rate is higher than in the Great Depression of the 1930s. African-Americans, Latinx, and the Indigenous have been the worst affected by these conditions. “Last hired and first fired,” they have been laid off, losing their incomes and their employer- paid-for insurance. That is, except for the “essential workers” who are disproportionately “minority” and therefore most exposed to the coronavirus.

Adding insult to injury, the U.S. has a president who ran on racist and nativist appeals to the bigotry of sections of the white population. This president has proven to be utterly incompetent and inept in dealing with any of the nation’s crises, but he has continued to direct blame onto Black and Brown people.

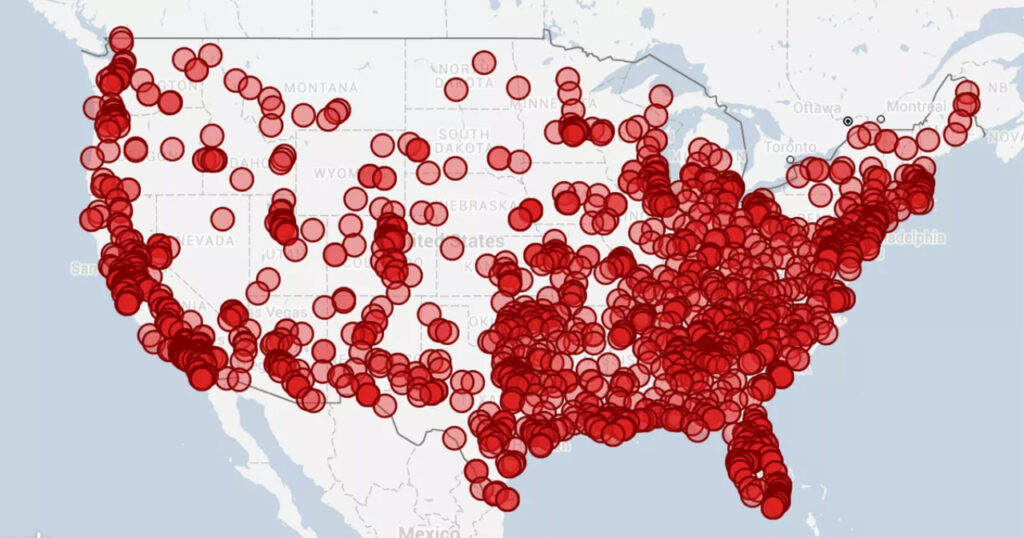

The murder of George Floyd by police, out in the open, publicly recorded, with witnesses calling on the police to stop, was a lighted match. The underlying rage of so many burst into flame. No one could justify the actions of the cops, not the establishment politicians, the police unions, nor the right-wing media. Not even President Trump. Millions of ordinary white working class and middle-class people were on the side of the Black population. Demonstrations began immediately and (at the time of writing) have not stopped. They have taken place in at least 140 cities and, overall, nearly 500 localities. The government almost immediately fired all four cops and charged one with murder; it has since expanded the charges to the other three. This is unlike the usual months-long foot- dragging.

The demonstrations have mostly been “peaceful” in the sense of law- abiding, if angry. Many white people have participated. Even some police have shown some support. But there has also been a fringe of violence and lawbreaking, including smashing windows of buildings, looting stores, fighting police, burning police cars, and setting fires to buildings (one police station was burned down). In big cities, there are reports of neighborhood watches being locally organized to prevent “outsiders” from setting off violence and destruction.

There is controversy about who is doing these violent actions (“violent” but almost entirely against things, not people). One claim is that it is done by (or led by) left-wing “antifa” activists and/or anarchists. There is also evidence that right-wing militants, including white supremacists, are mixing in, hoping to set off a “race war” or “boogaloo.” Whether there are many of these fascists is not known. To some extent blaming white “extremists of the left and right” serves to deny the real anger of Black people which could lead to such actions. (In any case, the looting of poor people of Target is nothing compared to the looting of billions of dollars in government aid supposedly for the unemployed or small businesses but instead grabbed by big businesses)

The authorities have varied in their reactions. The Democrats have tried to emphasize their sympathy with the protesters, while calling for police- enforced nonviolence and legality. They try to get the people to “join” with the police, and direct their anger to voting for Democrats. The right, after giving a quick nod to the righteousness of the protests, focused on the violence and destruction. They denounce the Democrats as being too “weak” toward the “rioters.”

President Trump, as usual, has posed as a tough guy to cover up his cowardliness. During demonstrations at the White House, he huddled in a basement bunker. He has called for the use of the military against demonstrators, announcing the need for “dominance,” and quoted, “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.” Meanwhile he posed for a photo- op in front of a well-known Washington Episcopal church which had some fire damage; to do this he had the military clear away a crowd of peaceful protesters with tear gas. (The Episcopalian hierarchy was displeased with him.) Hundreds of military personnel have stated that they will not serve to attack their fellow citizens who are peacefully asserting their rights.

While the police have posed as being cooperative in some places, in many places they have demonstrated what the protest is all about. They have assaulted marchers, shot rubber bullets at them, thrown them to the ground, beaten them with nightsticks, driven cars into crowds, cursed and threatened them, and probably aimed deliberately to provoke them to react violently.

Meanwhile the events are being used to whip up hostility toward anarchists. The extent of right-wing violent intervention has been played down or ignored. There has long been an image of anarchists as bomb throwers, assassins, and terrorists. It is true, that more than a century ago, a few anarchists did kill a number of government leaders, businesspeople, and ordinary people who were around them. More recently the “Unabomber” (who regarded himself as an anarchist) sent mail bombs to people he did not like. Otherwise this has been uncommon for a long time.

Anarchists have a wide range of views (as do liberals, conservatives, and Marxists). A large number are absolute pacifists. U.S. anarchists often get involved in demonstrations to serve as medics and legal aides. While it is counterproductive to urge disorganized violence, anarchists are correct to oppose trust in Democratic politicians and sweet-talking police officers.

Liberals make all sorts of proposals for improving the police. They have been doing so for decades. While some reforms may be useful, they have never made a big difference and never will. This society cannot exist without police. The conflicts between rich and poor, white and Black, men and women, different sections of the corporate rich, different sections of the working class, etc., make for a constantly clashing and conflictual society, in a continual state of almost civil war. It needs a state, with bodies of armed people (military and police), to hold it together. The charge that the removal of the state and its police would create chaos is exactly backwards. It is the chaos of capitalist society which requires the state. In a cooperative and free society of anarchist-socialism, there would be no need for the police.

Rather than focusing on “improving relations with the police,” it would be better if at least some of the young militants were to link up the issue of police brutality with other issues of oppression. This includes ideas of restarting the economy under the control of workers and working-class communities of all races and nationalities. It includes taking away the wealth of the one percent and distributing it fairly among the population in useful ways. It means dealing with the plague in a safe and healthy fashion.

By themselves, these demonstrations and rebellions have a tremendous impact on society. They show the power of the people when they take to the streets in direct action. The protesters are not relying on politicians to be political for them, but take matters into their own hands. They are not waiting for months to pass for the next election, but are acting right now while the issues are hot. In general, they have not aimed at civil disobedience, but many have been willing to keep on demonstrating even after the arbitrary curfews, which they know will often result in arrests.

Our rulers are fearful of these mass actions and vacillate between trying to bring it back into the occasional electoral booths and trying to beat the oppressed back. So far neither approach has worked well for the ruling class. And for even stronger leverage, the protests need to mobilize people as workers, using their potential power at the workplace. If the workers stop working, society grinds to a halt. If they start it up again, they could do so in a new and better way. Even now, bus drivers in New York and elsewhere have refused to take police and arrestees in buses from the demonstrations—with the support of their national union. Workers should demand support for the demonstrations from the unions. The slogan of a general strike should be raised, as a few radicals have already done. (However, the police “unions” should be thrown out of the union federation as agents of repression.)

Meanwhile neighborhood and local groupings, however informal, should further organize themselves and create citywide committees. Such committees could coordinate actions, decide on programs, and raise demands on the government.

This society is in deep crisis. Its present government might qualify as a “failed state,” it is so incompetent. The corona health crisis has been handled completely ineptly. But whenever it will be brought “under control,” the economic crisis will still be here for a long time. Meanwhile the climate catastrophe and ecological cataclysm are constantly worsening, giving us only decades to bring them “under control.” Racial oppression is an integral part of an overall oppressive and exploitative capitalist system. Capitalism has got to go.

These protests are a rebellion. They are evidence that the U.S. population is not forever passive and demoralized. There is great anger and a thirst for justice and freedom. This will not lead to an immediate revolution. But it raises the eventual possibility.

Original version written for Anarkismo.

Raining on the Parade:

Thoughts on the Black Lives Matter Movement (Part 1)

By Ron Tabor

July 4, 2020

For some time, I’ve wanted to write up my thoughts on the current incarnation of the Black Lives Matter movement. However, I’ve been hesitant to do so, for several reasons. First, I’ve wanted to wait to see how the movement develops, specifically, to gauge how much staying power it has and how it evolves politically. Second, I’ve needed time to sort out my feelings toward it.

Certainly, it’s been gratifying to witness such a powerful reaction to the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, and through that tragic event, to the killings of all the other Black people recently and historically victimized by the police and racist vigilantes. As others have noted, not only has the response been militant, it’s also been geographically widespread, occurring in tens if not hundreds and perhaps even thousands of cities and towns throughout the United States and around the world. The movement has also been racially/ethnically, gender-wise, age-wise, and religiously diverse, although largely dominated by young people. Beyond the demonstrations themselves, the issues of police killings and, more broadly, the racism endemic to US society (“systemic racism”) have evoked strong sympathy from large numbers of people from an array of backgrounds. Probably most surprising and encouraging, a considerable number of white people, including conservative whites, have expressed outrage at the killings and support for the protests. Hopefully, the movement will, at the very least, contribute to the ongoing enlightenment of the American people about the historical and current reality of racism in the country.

However, I am skeptical that the movement will have the transformative character that some people have envisioned. First, beyond some reforms of the practices of policing, not least to attempt to cut down on the number of Black people killed by police under questionable circumstances, I don’t see the main demand of the movement—to defund or seriously cut back on the resources devoted to police departments around the country—being achieved. (As far as I can see, the demand of some of the more radical people in the movement—to abolish the police altogether—is a complete non-starter in the current political environment.) This is because there is little support for this demand among the Black population, let alone among other sectors of society. There definitely is sentiment in favor of increasing the social resources devoted to the Black community, particularly its most oppressed layers. But in contrast to the views of many leaders of and participants in the Black Lives Matter movement, the majority of Black people do not want these resources to come at the expense of the police. On the most immediate level, this is because many, if not most, people in the community see themselves as needing protection, not primarily from the police, but from the violent street gangs and the other criminals that prey on members of their own community. The unfortunate fact is that the vast majority of the victims of violent crime in the Black community are victimized by other Black people, so-called “Black on Black” crime. This is not something the liberals, including and especially Black liberals, have wanted to talk about. So, until the problem of these gangs and criminals is addressed, or until some other means to protect people from these gangs is devised, the demand for a substantial reduction of the police presence in Black neighborhoods will receive very little backing from the residents of those neighborhoods.

To cut back on the presence of the police in many Black neighborhoods, let alone to eliminate it altogether, it is not enough simply to organize a few community defense squads, although I definitely support organizing such units. The Black gangs are armed with military-grade, automatic weapons, and they do not hesitate to use them. So, while perhaps in relatively low-crime areas civilian defense patrols may be suitable, this will not be the case in the poorest and most gang-plagued neighborhoods. If community defense squads in these areas were to receive the kind of weaponry and training the police get, then there is a good chance that such squads would turn into vigilantes who would prey on the communities they initially sought to protect. In light of this reality, even in the face of the recent demonstrations, the Black mayors of Washington, DC (Muriel Bowser), and Atlanta, Georgia (Keisha Lance Bottoms), have been asking for increases in the funding of their respective cities’ police forces, not reductions.

So, the real question that needs to be asked, if the police profile in Black communities is to be lowered rather than raised, is: how to deal with the economic, social, and cultural circumstances that give rise to the criminal gangs and to the other criminal elements that plague the Black community, particularly its poorest areas. This is not a question of devoting a relatively small portion of the funds of city, county, state governments, or even larger sums from the federal government, to provide a few more social services for these communities. It would require a national campaign, an enormous undertaking involving the mobilization of a vast quantity of financial and human resources.

This is because the economic and social situation in which the bottom third of the Black community finds itself today is dire. This is the section of the community that is considered, according to government statistics, to be living below the poverty line. And since we know that that line is drawn at an arbitrarily low level, we have good reason to believe that the number of Black people living in poverty today is higher, perhaps considerably higher, than the one-third figure would suggest.

(Prior to the crisis in 2008, roughly one-quarter of the Black community was deemed to be living in poverty, which represented a degree of progress compared to earlier times. However, the Great Recession hit Black people extremely and disproportionately hard. Huge numbers of people lost their jobs, their homes, their businesses, and their life savings. And despite the longest economic upturn since World War II that recently ended, for the most part, those victims of the financial crisis and the recession that followed have not made up the ground they lost.)

There are a number of reasons for this, but the most important, in my opinion, are three, all interconnected:

- The long and tragic history of Black oppression and white supremacy in this country – over two hundred years of slavery; the defeat of Reconstruction after the Civil War and the racist counteroffensive that followed it: the imposition of Jim Crow, debt peonage, prison farms, lynchings, and racist attacks on individual Blacks and on entire Black communities; the exclusion, for decades, of Black people from all but the most menial and unskilled jobs, and from the skilled trades unions, the ‘last hired and the first fired’; segregation in the military, in housing, and in education; denial of access to financing to start businesses, purchase homes, and pursue education; subjection to incessant police harassment and brutality, and political, judicial, and penal systems designed to maintain Black people in a subjugated status — in short, the violent maintenance of segregation and discrimination, and the suppression of voting and other democratic rights for decades, up to the victories of the Civil Rights movement in the mid-60s.

- The continuation, both overt and hidden, of segregation and discrimination in jobs, housing, access to financing and to good schools, etc., of police harassment and judicial injustice up to the present, and along with this, deep-seated racist attitudes on the part of many, if not most, members of other racial and ethnic groups, and not just whites.

- The psychological demoralization of that part of the Black community that remains stuck at the bottom of society, people who have not been able to pull themselves up into the regularly employed, socially-stable layers of the working class, let alone into the middle class.

A subset of this extremely oppressed section of the Black community correlates roughly with what Marx called the “lumpen proletariat.” In Marx’s analysis, the lumpen proletariat is located beneath the “proletariat,” the working class proper, in the structure of capitalist society. In the United States today, it consists of homeless people, panhandlers, scavengers, and street hustlers, the permanently unemployed, those trying to survive on (often illegally-obtained) public assistance and off-the-books jobs, and the partially employed. It also includes those, mostly young men aged 15-29, who are involved in violent criminal activity: either (1) those who, individually or in small groups, engage in robberies, muggings, carjackings and home invasions; or (2) those who are involved in the organized criminal gangs, most of which are involved in the drug trade.

Many of the people who make up this layer of the Black community are incapable of holding, or are unwilling to hold, full-time jobs, even if these were available to them. Many, due to the poor schools in their communities and other factors, are functionally illiterate. Many don’t have the self-discipline or the motivation to get to work on time and on a consistent basis. Some individuals, when they do get jobs, stay on them for a month or two, then quit and spend their income, mostly on getting high. Perhaps most of them, instead of looking for work, choose to hustle, to “get over”, and/or to engage in criminal activity rather than work a “nine-to-five” for “chump change.”

Like all social groups, this layer in the Black community has evolved a culture—a set of social and psychological attitudes, mostly negative, toward work, self-discipline, education, saving money, and toward the rest of society, from which they are excluded and alienated—that renders them incapable of being successful or even of participating in that society. (This is not just a characteristic of the Black community. The poorest strata of other racial/ethnic groups, such as Latinos and whites, share a similar culture. However, because of the specific, racist, history of this country, the social layer I am discussing is proportionately larger in the Black community than in other racial/ethnic groups.) This culture both defines these people’s place in the social structure of contemporary society and connives with that structure to keep them there, a culture that is generally passed on, consciously and unconsciously, from generation to generation. The result, a combination of specific historical and contemporary economic and social circumstances and a cultural/psychological reaction to them, is a distinct social layer whose conditions of existence, outside of a drastic change in economic, social, and political conditions (i.e., a revolution), are not likely ever to be substantially improved.

From the point of view of the rest of society (and not just white society), this group of people at the very bottom of our social structure represents a “problem” that society, as it is currently organized, lacks both the will and the resources, financial and human, to solve. So, instead of remedying it, society chooses to try to contain it. And the chief instrument it uses to do so is the police.

Members of this layer of the Black community (and similar layers in other oppressed communities), particularly the young men involved in the gangs, are responsible for a large portion of the violent crime that occurs in the cities of the country, and in particular in the communities in which they reside, far out of proportion to their numbers in the population as a whole. (The criminal sectors of wealthier ethnic groups, e.g., Anglo-Saxons, Italians, Jews, Irish, Russians, Armenians, Asians, and others, commit their crimes in more genteel circumstances – so-called “white collar” crime: financial embezzlement, fraud, blackmail, etc., criminal activity that involves a lot more money.) As a result, a form of social conditioning arises that, in the context of the racist attitudes of large sections of the population, leads people, and especially the police, to associate Black people, particularly young Black men, with criminal activity. So that when a police officer, particularly a white person with racist attitudes, sees a young Black man, his/her/their almost instinctive reaction is to see that person as a criminal, or at least to suspect that he might be. Aside from the hostility and vicious intent of conscious white supremacists on the police forces of this country (and there are many), this, in my opinion, explains a good number of the police killings of Black people that have occurred historically and recently. And because of this, such killings will continue to occur as long as the current social system remains unchanged.

Until the existence, the characteristics, and the circumstances of this extreme oppressed and demoralized layer of the Black community, including its criminal elements, are explicitly recognized and frankly discussed, very little of what the Black Lives Matter movement and its allies are talking about and calling for has much relevance. Toppling monuments, renaming buildings, writing books and articles, making anti-cop TV shows and movies, holding lectures and organizing discussions about “systemic racism,” legalizing marijuana, expanding affirmative action programs, “reimagining” policing, eliminating cash bail, instituting job-training programs in prisons, etc., while worthy, are not going to get close to addressing the needs of the people I am describing. As a result, such measures will neither eliminate police killings nor substantially lower the profile of the police in our society, especially in racially oppressed communities.

The existence of this extremely oppressed sector of the Black community was one of the shoals on which the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 60s foundered. If that’s what happened then, when the US economy was at its apex and US global hegemony was at its strongest, what are the chances that the needs of these people can be met today, when the economy, at its best, barely expands and when the US is struggling to maintain its global position? As we’ve been saying for decades, to address the needs of these people, and in fact the needs of all working class and oppressed people, would require a revolution that turns our entire economic, social, and political system upside down.

Raining on the Parade:

Thoughts on the Black Lives Matter Movement (Part 2)

By Ron Tabor

August 13, 2020

Introductory note:

Two people in our group have told me that they consider the first part of this document to be excessively critical of the Black Lives Matter movement. My initial response to the movement was, indeed, very positive. I indicated this in an email I posted to the list soon after the movement erupted. I also proposed that our group adopt Wayne’s statement (written for another venue), which was enthusiastic in its evaluation of the movement. As the movement developed, however, my attitude toward it became increasingly critical. I attempted to explain my reasoning in the first part of this document and continue along these lines below. I urge all those who maintain a more positive assessment of the movement than the one I have presented to write up comments to this effect and post them to the list.

Beyond what I wrote in the first part of this document, I have additional criticisms of the Black Lives Matter movement.

First, I was disturbed by the violence directed by many demonstrators (beyond the racist infiltrators and undercover police agents) toward small businesses, many of them owned by members of racial, ethnic, and religious minorities (a lot of them immigrants), and by women and LGBTQ people. Although such “trashing” was understandable in the first few days of the movement, after that, it seemed to me to be tactically counterproductive, gratuitous, and even cruel. (Why run the risk of alienating possible allies?) And as it turned out, this aspect of the movement has generated hostile reactions in several (Black and Latino) communities around the country and perhaps more.

More fundamentally, I was and still am appalled at the lack of any serious analysis on the part of the Black Lives Matter movement of the “racism” it denounces as the cause of the police killings of Black people and the other aspects of Black oppression. What, exactly, is racism? What are its sources? And how can it be eliminated? As far as I’ve been able to tell, the movement’s leaders, spokespersons, and sympathizers have come up with nothing more than describing racism in the United States as “systemic” and/or “structural,” without further analyzing what these words mean. “Systemic” implies the existence of a system, but the movement has not even gotten around to the task that Carl Oglesby, the SDS spokesperson at the anti-war demonstration in Washington, DC, in November 1965, urged on the movement of that era. “We must name the system,” he said. I’ve heard no mention on the part of the BLM movement of “capitalism,” let alone other, possibly deeper, sources of “systemic” racism. (Given that two of the movement’s founders, Patrisse Cullors and Alicia Garza, consider themselves to be Marxists, this omission is particularly egregious.) And lacking an analysis of racism, its sources, and its roots, how can the movement come up with substantive proposals for what would be needed to get rid of it? (As I mentioned in Part I of this article, nothing that’s been mentioned thus far will get anywhere close to addressing, let alone solving, the oppression of Black people in this country, particularly that of the poorest layers of the community.) Not the least of the problems caused by this analytical lacuna is the ease with which the movement’s slogans have been coopted by the US liberal establishment, in the form of the Democratic Party. That party’s candidate for president, Joe Biden, has already vowed to “root out systemic racism.” (Really?)

I’ve also been disappointed that the movement has shown little desire or ability to move beyond the categories and demands of identity politics. This is most concisely expressed in its insistence that the only demand, and the only meaningful issue at stake in the protests, is: “Black Lives Matter,” and that by implication, other lives do not matter. Most crucially, the BLM movement (as it did in its original incarnation in 2013) has explicitly rejected the slogan, “All Lives Matter.” To the leaders of the movement, to say that “all lives matter” is to say that Black lives really don’t matter. By this logic, to say that all lives matter, a view that, taken literally, any morally-concerned person ought to hold, is, by definition, racist.

I believe this position (rejecting the slogan “All Lives Matter”) is a mistake. I understand where it’s coming from: that throughout US history, the needs and demands of Black people have always come last, when they’ve been recognized at all. But to just flip this over (that is, to reject the slogan that “all lives matter”) is logically and politically questionable. Not least, it implicitly accepts the historic racial hierarchy that it claims to want to overthrow. It also limits the possibility of winning allies to the movement. And it hands the racists (such as Donald Trump) both a screen behind which to hide and a tool with which to mobilize people who are not Black behind their racist banner and program. “See,” such demagogues can say (and are saying), “the real aim of the BLM movement is not racial equality or justice, but Black supremacy, the triumph of identity politics and Political Correctness. In contrast, we are the only ones who really believe that all lives matter.”

(Anecdotal evidence suggests that the movement has doubled down on this position. At recent demonstrations, BLM protesters have accused anybody who raises the slogan of “All Lives Matter” or otherwise questions the movement’s stance on this issue of being a racist and/or a police agent.)

As I mentioned, such an approach hurts the chances of building real — meaningful and durable — solidarity with the movement. Instead, it limits the basis of potential support to those of sympathy and guilt. But if the movement is to have any real chance of reaching its goals (even its most minimal ones), it needs real — strong and steadfast – allies. And such allies are not won by appealing exclusively, or even primarily, to sympathy and guilt, which are, by their nature, unstable. (This is one of the main lessons of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, when much of the support — personal, political, and financial — of the movement on the part of middle-class white liberals dried up virtually overnight when the leadership of SNCC moved in a more militant and nationalist direction, specifically, when, under the leadership of Stokely Carmichael, it took up the slogan of “Black Power.”) Staunch allies can only be won, and a solid movement built, on the basis of mutual self-interest, specifically, if the movement explicitly and aggressively attempts to build solidarity among all people who are victims of police violence and, more broadly, of racism. And as we know, Black people are not the only victims of these evils, although they are victimized out of proportion to their numbers in the population. Other racial and ethnic minorities, particularly but not exclusively Latinos, are also victims. Women and LGBTQ people, particularly if they are Black, Latino, and/or poor, are victimized by the police. Not least, poor white people are victims of police violence; in fact, the vast majority of people killed by the police in this country every year are white, and usually poor.

(As an aside, I wish to indicate here my view that, as paradoxical as it may seem, poor white people are victims of racial oppression, of the racist nature of American society. The profound contempt in which they are held and with which they are treated by many sectors of the US population, as when they are referred to as “poor white trash” and/or “trailer trash,” has its roots in racism. The implicit structure of this attitude is this: We all know that we live in a racist society, a society built on white supremacy. Yet, even in such a society, with all the advantages (“privileges”) white people have, you (poor whites) are still on the bottom. That makes you even worse, even more pathetic, than Black people.)

I believe the staunch commitment the Black Lives Matter movement has shown to “identity politics” is a serious drawback. We can all agree, I believe, that there’s some truth to such politics. Specifically, we can see that our society is, and has always been, centered around a structure of relative advantages and oppressions based on certain personal/identity characteristics, a mesh of interlocking racial/ethnic, gender/sexual hierarchies, which puts some on the top and others at the bottom. More specifically, we live in a white supremacist and patriarchal society, in which people who are not white, not males, and not heterosexual suffer discrimination, social condemnation, and abuse, whereas people who are white, male, and heterosexual not only do not experience such oppression, they also have greater access to power, money, and other privileges in our society. We can also admit that this is unjust and that consequently we should support and participate in struggles to end this situation, to do away with such injustice and oppression, and to build a society in which people who belong to all oppressed groups and identities are treated equally and fairly.

Yet, I think we can agree that this identity politics narrative is not the entire story. Most importantly, it leaves out the question of socio-economic class, that is, where a person sits within the economic hierarchy, which is fundamental to the social system under which we live. I believe that where one exists in this hierarchy of wealth and power is more important, more socially significant, than one’s identity characteristics as defined by contemporary identity politics. Certainly, the various forms of identity advantages and oppressions affect where one finds oneself in the economic hierarchy, but this does not overcome the fundamental importance of that hierarchy. While we can agree that, in general, white people have many advantages over (are “privileged” vis a vis) brown and Black people, when one looks toward the bottom of our society and makes comparisons between individuals and families in those strata and individuals and families who live in comfortable or even luxurious circumstances, those identity advantages and “privileges” start to look rather abstract. Can it truly be said, in terms of the concrete circumstances of their lives, that poor white people are “privileged” vis a vis wealthy Black people? Are, say, Barack and Michelle Obama, who are now multi-millionaires, more oppressed than a white, male, laid-off coal miner in Appalachia, looking for work, striving to stave off foreclosure of his home, and seeking solace in alcohol or opioid drugs? Is a poor, white, single mother working two or more minimum-wage jobs, and caring for three children in a dying mid-western city, somehow “privileged” in comparison to a woman member of the economically-secure Black middle-class? To ask such questions is to answer them. To be frank, I believe that calling a poor person of whatever identity characteristics in this society “privileged” is absurd.

The blind spot that identity politics has toward the issue of the economic hierarchy has its source in its definitions. To these politics, where one sits in that hierarchy, e.g., whether one is rich or poor, does not count as an identity category. As a result, a poor white man is simply thrown into the “privileged” categories of “white” and “male,” along with people who have real power in our society, such as corporate executives, powerful politicians, or top military or police officials. As a result, through a logical sleight of hand, this person’s very real oppression is made simply to disappear, along with the oppression of millions of other white working-class and poor men. How convenient for the capitalist elite!

One of the other problems with identity politics is that it accepts the limits of our current social system (and consequently represents no threat to it). This is because such politics sets up the various identity groups, taken singly or in various combinations, to compete with each other for shares of an economic pie which, even in the best of times, grows very slowly. This is one of the main reasons why the members of the ruling elite love identity politics, while they despise, and in fact are petrified of, any talk of class politics, the class struggle, that is, uniting poor, working-class, and lower-middle-class people of all identity groups in a united struggle against the system.

It’s obvious that the Democrats aggressively embrace identity politics; forging a coalition of the officially-oppressed identity groups is the key to their political strategy, both during elections and in between. Darryl Pinckney, in an essay, “’We Must Act Out Our Freedom,’” in the August 20, 2020, issue of the New York Review of Books, paraphrased Black Georgia politician (and rising star in the Democratic Party) Stacey Abrams to this effect: “Abrams blames the concentration on class for holding back the development of an identity politics that relates more to the “intersections” that governed her life growing up. She looks to an identity-based new majority coalition of the non-white, women, and LGBTQ, and offers statistics showing that the number of voters in these categories will continue to be larger than we’re used to seeing. (In other words, “Anything but class!”)

Ironically, the Republicans also embrace identity politics. A central aspect of their strategy is to appeal to the one identity group that is left out of (and in fact is demonized by) the identity politics narrative of the liberals: working-class and poor white males. These are the people whom the liberals (and most of the left) write off as being “privileged” (and incorrigibly racist) and whose legitimate concerns are arrogantly dismissed as being motivated by nothing more than “racial resentment.”

Yet these are precisely the politics the Black Lives Matter movement so militantly embraces and seems so reluctant to give up. Are all working-class white men (many of whom were outraged at the deaths of George Floyd and the other Black people recently killed by police and even marched in the streets) the enemy? Are their struggles and needs simply to be ignored? Are they to be assigned the political task of merely supporting the struggles of Black people? Or do we wish to build a joint struggle with them, and with all oppressed people, to fight for all of our freedom?

I believe we have to firmly reject identity politics and go beyond them. We have to militantly oppose the Democrats’ strategy of building a coalition around the liberal version of identity politics (along with the converse version promoted by the Trump Republicans), which is doing so much to stoke the tragic political, cultural, and racial polarization of the country. Against that approach, we contrast our own strategy and vision. We seek to build a movement that promotes the fight for full rights for all “identities” while simultaneously seeking to unite all working-class and oppressed people in a common struggle to overthrow the ruling elite and the social system over which it presides.

Fight for Our Vision

Against Uncritical Cheerleading

By Ron Tabor

August 20, 2020

I would like to express my disagreement with what appear to be the sentiments expressed by much, if not most, of the left toward the Black Lives Matter movement. This is to go along with whatever the protesters involved in the struggle want to do and/or say at any given time and simply encourage them, because they are out there fighting the cops in the streets of Portland, Seattle, and other cities. Implied in this attitude is that the left not only should not criticize the movement but that it does not even have the right to criticize it.

I strongly disagree with this attitude. In contrast, I think that the revolutionary left, and our tendency especially, does have something, and something very important, to say to the young activists involved in the Black Lives Matter movement, and that we have the right, and even the duty, to say it.

The attitude I have described comes down to nothing more than uncritical cheerleading for the current (liberal) movement and its current (liberal) politics. This position goes against everything our political tendency has ever stood for. Being forthright, open, and honest about what we believe, what we think, and what we advocate has been a defining characteristic of our tendency, from the moment it was born up until the present. It was the central component of our platform in the faction fight in the International Socialists, in which we argued that it was the job of revolutionaries, in the words of Leon Trotsky, “to say what is,” that is, to tell the truth. Specifically, this meant (as we put it then) holding up the banner of revolution, to make clear that the only way to win lasting social and economic gains and to liberate humanity is for the working class to carry out a socialist revolution that overthrows capitalism and establishes the democratic rule of that class and the other oppressed people in our society. This was in contrast to the I.S.’s strategy of hiding one’s politics and pretending to be the “best builders” of whatever movement their activists were involved in, while seeking to entice that movement to the left through the dishonest, manipulative, and bureaucratic “next-step-to-the-left” method. (Not only did the I.S. members hide their own politics, they also acted like policemen in the organizations they controlled, working to prevent other, more honest, activists from raising their politics.) And everything we’ve done since then, in whatever form our tendency took, in whatever movements we’ve been involved, and in whatever political and theoretical struggles we’ve been engaged, has been consistent with our political honesty, with our belief that it’s crucial to forthrightly advocate for revolution and to criticize the movements and struggles we’ve been involved in from that standpoint. And insofar as we have a reputation on the left (and we do have a reputation), it’s because of: (1) the informed and thoughtful nature of our political analyses; and (2) our commitment to stating as clearly, as honestly, and as forthrightly as we can, what we believe and where and how we disagree with the movements and the organizations in which we’ve been active.

But the logic of the left’s current attitude is to jettison all this and instead to become uncritical cheerleaders of the existing Black Lives Matter movement (and by implication, all future movements), that we cease raising our criticisms of what that movement is doing and saying, and that in particular, we stop criticizing the movement because it’s not revolutionary. This position comes down to taking on the I.S.’s historic role of being the policeman of the left, determining which individuals and groups, and under what circumstances, have the right to criticize the Black Lives Matter (and all future movements, particularly if they involve young people). It’s also a resurrection of facets of the Stalinists’ politics of the 1960s, which, among other things, insisted that white people were not allowed to criticize “Black leadership” (not even if such “leaders” were demagogues, criminals or police agents) and that it was impermissible for anyone, in any way and at any time, to criticize the Soviet Union, because the Stalinist regime was in the “front-line of the struggle against American imperialism.”

In regard to the Black Lives Matter movement (and in fact to all mass movements), it seems to me that we have the obligation to tell the truth as we see it. And the most important aspect of the truth in the current situation is the question of revolution, because the idea that the police can be seriously defunded, let alone abolished (or that police killings of Black people can be substantially reduced), under our current social system is absurd. And if we truly believe that a revolution is needed, then we should say so, loudly and clearly. If we do not, we will merely be helping to set up the movement for inevitable defeat and the demoralization of its participants. Already, the political base of the Black Lives Matter movement is shrinking, not least because a considerable majority of Black people in the country not only do not want to defund (let alone abolish) the police but want more, and better, police. This is largely because, as I write, the Black communities in many US cities are being ravaged by a wave of gang-related shootings. This is not to mention the question of whether, as some Black activists have begun to wonder, the current violent confrontations occurring in Portland and elsewhere are no longer helping the cause but instead are becoming a liability, a “distraction.”

I also disagree very strongly with the “tactic” of tearing down monuments. First, destroying the monument to Hans Christian Heg, a Norwegian immigrant who devoted his life to the destruction of Black slavery and perished leading a regiment of volunteers during the Civil War, was an ignorant and sacrilegious act, an insult to a man who deserves our admiration and respect, not our condemnation. And I think we should say this and not gloss over it or excuse it. It’s also a callous dismissal of the rights of those people in the country who may not want to see the destruction of monuments, and certainly not without a national discussion of the issue (which might turn out to have considerable educational value in the struggle against racism). All the people in this country have a legitimate stake in the monuments in question and have a right to have a say into how they are treated, e.g., whether they are demolished, removed from their current sites, or whatever. Yet, the uncritical attitude of much of the left seems to be that anyone who does not agree to allow the Black Lives Matter protesters to tear down whatever monuments they want, whenever they want to, is, by definition, a hard-core racist whose political rights are not worth recognizing. It seems to me that we should be defending the (democratic) rights of all the people in the country and not just those who happen to agree with us. This has been the historic position of our tendency; moreover, our vision of socialism/anarchism can be seen as the radical extension of democratic rights, not their destruction.

Last, if we think, as I do, that participating in “call-out” and “cancel culture” and otherwise promoting militant Political Correctness (which seems to be a basic characteristic of the Black Lives Matter movement) is totalitarian, then we should say so, openly and honestly, and not just go along with it uncritically. (And if we don’t agree about this, then we really do need to have a discussion, because I refuse to be part of a political tendency that does not, militantly and forthrightly, condemn such totalitarian practices.) In sum, I believe that we have the duty to criticize the Black Lives Matter movement (and all mass movements) where, when, and how we think it’s appropriate to do so.

As for whether we have the right to criticize the current Black Lives Matter movement and its leadership, all I can say is:

- Nobody has to earn the right to criticize anything or anyone. To put it bluntly, the idea that only some people have the right to have an opinion (to criticize) is the essence of totalitarianism.

- More specifically, nobody in our tendency has to earn the right to criticize the Black Lives Matter movement, or any other movement.

None of us has any reason to feel ashamed of or guilty about who we are, what we have or have not done in the past, or what we are doing at the moment (that is, whether we are or are not, right now, fighting in the streets). We don’t have to prove anything to anybody!

Our tendency has been around for over 50 years. Some of us have been politically active for nearly 60 years. During that time, we’ve devoted our hearts and our souls to the movements for social change and to the struggle for the revolutionary transformation of society, whether we called that “socialism” or “anarchism.” Aside from the many, many hours we’ve spent in meetings; holding discussions; organizing study classes; reading and thinking; participating in debates and conferences; handing out leaflets; writing, publishing, and selling newspapers; walking on picket lines, and marching in mass demonstrations, we’ve been tear-gassed, gotten arrested, and spent time in jail; we’ve fought against and have been beaten by the cops; some of us have suffered permanent injuries as a result of these battles.

We also remained committed to the cause of revolution when, during the 1970s and 1980s, it was no longer “cool” to do so, when so many of our generation gave up the struggle and made their peace with this disgusting society: people such as Bill and Hillary Clinton, who went on to fame, fortune, and power as political agents of the ruling class; people such as Jerry Rubin, who stopped pretending to be a revolutionary and made millions with his networking salons; people like David Horowitz, Ronald Radosh, Sol Stern, and David Brooks, who went from the Left over to become well-paid theoreticians and spokespersons of the newly-fashionable Right. Later on, in the 1990s and since, we watched as several generations of activists in the anarchist movement came and went, and as many former revolutionaries, including some of our own comrades, became liberals and enthusiastic supporters of the Democratic Party.

Why, given all this, should we feel guilty or ashamed that we are not now in the front lines of the demonstrations in Portland, Seattle, and in other cities, where we don’t even live? Why does this mean that we are not allowed to raise our criticisms of the Black Lives Matter movement? Why, more broadly, does this mean that we have to bow down to every new generation of liberal activists that comes down the pike: the young (and not so young) feminists who saw Bill and Hillary Clinton as the answer to their prayers; the Black kids who enthusiastically mobilized behind Barack Obama (only to become completely disillusioned by what he did and what he failed to do while in office); the activists in the Occupy movements; the high school students who allowed themselves to be used as shock troops in the liberals’ campaign to roll back gun rights and repeal the Second Amendment to the Constitution; the many people, young, middle-aged, and old, who allowed the pied piper known as Bernie Sanders to lead them into the death trap of the Democratic Party; and the current generation of activists who are involved in the Black Lives Matter movement. Given what’s happened to the liberal and radical activists in the past, there’s little reason to believe that this latest cohort will be around two years from now, let alone 10, let alone 50. But, we’re still here. Despite this, we’re supposed to sit in awe of what the “young folks” are doing, simply cheer them on, and refrain from raising our differences with and criticisms of them. This is just liberal pandering. It’s also patronizing, condescending, and irresponsible.

And if one believes that, even now, even after all that’s happened, we should give up our right, our duty, to raise our differences with, even to criticize, the current movement when we feel that it’s going awry, then why not follow this thought to its logical conclusion? Why not propose that we turn our political tendency into a team of (liberal) cheerleaders of whatever the young people do? Why not suggest that we become merely a discussion network of former revolutionaries? Or, better yet, why not make a motion that we dissolve our group altogether? That way, we can safely retire to our couches and our favorite armchairs and get our news and take our political direction from the liberal “experts,” such stooges of the Democratic Party (and nauseating blabbermouths) as Van Jones and Rachel Maddow. Speaking for myself, I’m not ready to do this.

(Ron Tabor has requested that the following two articles be included in The Utopian as a further contribution to the discussion.)

The Politics of Riots

by Cathy Young (Reprinted from ARC)

After two months of relative quiet, violent protests have exploded again in Kenosha, Wisconsin, sparked by the police shooting of a 29-year-old black man, Jacob Blake. The timing—the week of the Republican National Convention—could not have been better for the GOP: the chaos and destruction awaiting America if the Democrats win the White House was the dominant theme in Donald Trump’s acceptance speech.

It’s a specious argument, considering that the chaos is currently happening on Trump’s watch and that both people on the Democratic ticket, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, have condemned the rioting and looting. And yet progressives’ responses to this summer’s troubling events may well end up hurting the Democrats.

There is no question Trump has fearmongered and exploited unrest in several cities. But to deny that what has happened in Kenosha, what’s been happening in Portland, and what happened in Minneapolis and a number of other places qualify as riots is bizarre.

It’s not the first time CNN has taken a well-deserved drubbing over apparent riot denialism.

On August 26, there was the infamous chyron referring to “fiery but mostly peaceful protests,” even as correspondent Omar Jimenez stood in front of a burning building. It’s true that the report itself wasn’t particularly bad, noting that the protests were peaceful during the day but grew violent toward the evening; the chyron just compressed that in an unfortunate way. But for many, this line is emblematic of a larger problem with media coverage of the protests.

Take, for instance, the scant coverage of the fatal shootings of two black teenagers, ages 16 and 19, in Seattle’s “Capitol Hill Occupied Protest Zone” (CHOP) in June—at least compared to the fatal shooting of two protesters in Kenosha, Wisconsin by 17-year-old armed militia member Kyle Rittenhouse. Several more people were wounded in at least four separate CHOP shootings between June 20 and June 29, the last of which was carried out by the zone’s security patrol (and finally prompted the city to shut the place down). The only known perpetrator is still at large. The parents of one of the victims, 19-year-old Lorenzo Anderson, have sued the city for negligence, but this too has received little attention outside the local and conservative press.

Notably, on June 11, Seattle’s progressive mayor Jenny Durkan waxed poetic on Twitter defending CHOP (initially CHAZ for Capital Hill Autonomous Zone) as a “peaceful expression of our community’s collective grief and their desire to build a better world.” Media outlets such as The Daily Beast and Politico also chimed in to rebut conservative claims of a far-left reign of terror inside CHAZ/CHOP and tout it as a social justice-flavored street festival. But a recent New York Times report by Nellie Bowles makes it clear that, while the conservative alarmism may have been overblown, the reality was pretty bad.

This is part of a pattern—not only among journalists but among politicians. Many on the right overhype the “cities are burning” theme (in Commentary, Abe Greenwald says we’re seeing nothing short of a violent revolution); many on the left, including ostensibly mainstream journalists, minimize or excuse the mayhem. This summer, major liberal publications—Slate, TheAtlantic, The New Republic—have run material sympathetic to rioting and looting, both as instruments of change and as valid expressions of anger and despair. In a tweet about the events in Kenosha, prominent journalist Julia Ioffe suggested that the people who burn and loot are “frustrated by the continual and unpunished killing of Black people by police.” (Never mind that quite a few black activists have condemned the rioting by mostly white anarchists as “white spectacle.”)

Some truly disturbing stories stayed practically off the radar. Thus, the apparent targeting of the Jewish community centers and businesses during the riots in late May-early June in Los Angeles (including the defacement of synagogues with anti-Semitic graffiti), received virtually no coverage outside the Jewish press and was not condemned by a single politician.

The assault in Madison, Wisconsin on state senator Tim Carpenter, a progressive Democrat who sustained injuries to his head, face, neck and rib after being knocked down, punched and kicked by two protesters—both white women, one a social worker and the other a licensed therapist—was reported in the national media but received relatively little attention. (Not to play “what if the shoe was on the other foot,” but one can imagine how big the story would have been if his attackers had been Trump supporters.) A column for The Cap Times, a digital newspaper in Madison, blamed Carpenter for his own assault because he tried to film a video “against the protesters’ will.” Wisconsin Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes, a progressive Democrat, mustered a feeble condemnation on Twitter, saying only that he was “very disappointed” by what happened to Carpenter but reserving far stronger words for “far right provocateurs” who have “pushed people to this point.”

Meanwhile, the bizarre claim that looting is only about “property” and that calling it violence cheapens human (and especially black) lives had been made by Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times writer Nikole Hannah-Jones, author of the “1619 Project” exploring American slavery, and echoed by many others including Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Connecticut). After the rioting broke out in Kenosha, Murphy initially tweeted a condemnation of police brutality and vigilantism as well as looting and property damage.

An hour later, he deleted it, explaining that he had been told it equated murder with property crime.

But this specious argument ignores several highly salient points. One, looting and property destruction have a devastating effect on human lives, both those of the owners and those of the communities. (A thread by British reporter Josh Glancy documenting the devastation in Kenosha—particularly in black neighborhoods—searingly conveys this point.) Two, looting and arson are a hazard to human life in a much more literal sense. In July, a burned body was found in the debris of a Minneapolis pawnshop torched during the riots in May; the male victim had apparently died in the fire. And on June 2, David Dorn, a retired police officer in St. Louis, Missouri was shot to death while defending a store from looters—his final moments, horribly, livestreamed on Facebook as he lay bleeding on the sidewalk. (This is another story that has received far less attention than it should have.)

Maverick leftist Michael Tracey, who has traveled extensively across areas that experienced riots this summer, has argued that the mainstream media have persistently downplayed the extent of the violence and devastation inflicted on these communities, as well as the role of non-local anarchists and other hardcore leftists—“likely because of the belief that [reporting this] could in some vague sense ‘help Trump.’” While Tracey has his own biases, he makes a strong case, and his view is shared by many people of various political stripes—even those who are solidly anti-Trump. For those who are vacillating, the belief that the media (Trump’s archenemy) are unreliable and unfair and that many Democrats are sympathetic to the rioters could make a difference.

Narratives of Violence

Unfortunately, the events in Kenosha lend a lot of credibility to the criticism of both the media and progressive politicians.

It seems very likely that Blake’s shooting, with seven shots fired in his back at close range while he was trying to get into his car, involved excessive force. However, it now also seems that the initial narrative of the shooting—laid out, for example, in this Washington Post editorial—in which Blake was an innocent man who was trying to break up a fight between two women and got shot in the back by the cops for no discernible reason was false.

Blake, we now know, was being arrested on an warrant stemming from a May 3 incident in which he allegedly broke into his ex-girlfriend’s residence, sexually assaulted her, then removed her car key from her purse and absconded with her truck (which he left at her sister’s residence in Illinois the next day). On Sunday, August 23, the same woman, Laquisha B., who has three children with Blake, called the police to say that he was back at her place despite a no-contact order. The officers who answered the call were advised of the outstanding warrant and tried to arrest Blake; a scuffle ensued during which the officers used tasers twice. According to the Wisconsin Department of Justice, Blake also had a knife on the floor on the driver’s side of his SUV, though there is no evidence that he tried to use it. His three children were in the back seat of the car—which certainly makes the shooting more horrifying, but also raises the possibility that the cops thought the children would be in danger if their father drove off with them.

Seven shots seems shockingly excessive. On the other hand, it seems very unlikely that this was an act of wanton violence by racist white cops, as it has been presented. Perhaps The Washington Post should have waited for at least some facts to emerge before publishing editorials.

Some right-wing Twitter users have claimed that Blake is a “child rapist”; this is a false rumor, based on misrepresenting the statute under which he was charged. However, the actual charge is quite ugly: Laquisha B. told the cops, who found her badly shaken and distraught, that Blake had barged into her bedroom while she slept, woken her up to demand his possessions (“I want my shit”), abruptly reached under her nightgown and jammed his finger inside her vagina, then sniffed it and accused her of having been with other men. She also told the police Blake had physically abused her on previous occasions when drunk.

So far, these are allegations; conservatives who worry about the presumption of innocence in campus sexual assault cases should remember that Blake has not told his side of the story and has not been found guilty of anything. (After the shooting, Blake’s ex described herself to reporters as his “fiancée” with no mention of the abuse charges.) On the other hand, by progressive rules, Blake should be regarded as a rapist, and defending his innocence would require making the very “problematic” argument that his ex either lied or exaggerated the incident.

Of course, even if Blake is a sexual and domestic abuser, his alleged offenses do not call for summary execution. But the picture that emerges from the complaint surely adds to the probability that he was behaving violently in the confrontation with the cops and that they were justified in at least some use of force. These are relevant facts, largely swept under the rug in media accounts depicting Blake as a loving family man and a “doting father.” Even now, the original narrative of Blake being shot seven times while trying to break up a fight remains entrenched on progressive Twitter.

The biases in many accounts of the shooting of three Kenosha protesters (two of them fatally) by 17-year-old Illinois resident Kyle Rittenhouse have been even more blatant. No one should be painting Rittenhouse as a hero, and Tucker Carlson has been rightly criticized for suggesting that it made sense if “17-year-olds with rifles decided they had to maintain order when no one else would.” On the other hand, a Washington Post column by Erik Wemple blasting Carlson omitted any mention of fairly strong evidence that Rittenhouse was being attacked when he fired. (So did this Wonkette blogpost calling Rittenhouse a “homicidal maniac” and referring to the claims of self-defense as the work of “Nancy Drews on Twitter.”)

Meanwhile, an Associated Press story says that the first victim, Jacob Rosenbaum, “followed Rittenhouse into a used car lot, where he threw a plastic bag at the gunman and attempted to take the weapon from him.” But video of that moment clearly shows Rosenbaum chasing Rittenhouse, not just “following” him, and strongly suggests that the thrown plastic bag had some hard object inside it (it doesn’t float but makes an arc and falls). Indeed, a New York Times article tracking Rittenhouse’s movements notes that “footage shows Mr. Rittenhouse being chased by an unknown group of people into the parking lot of [an auto] dealership.”

However, the Times description of the video which shows the shooting of Anthony Huber and Gaige Grosskreutz omits some vital details. The article notes that as Rittenhouse runs away after shooting Rosenbaum, “he trips and falls to the ground [and] fires four shots as three people rush toward him.” In fact, those people attack him: The video clearly shows that when Rittenhouse falls, the third man kicks him in the head and then Huber hits him with a skateboard.

The media have also danced around the fact that both Rosenbaum and Huber had criminal records that included violent felonies. Rosenbaum had served time in an Arizona prison from 2003 to 2016 after being convicted of “sexual conduct with a minor” and racked up nine disciplinary infractions for assaults on staff—many involving “throwing substances”—plus one for assault with a weapon, one for arson, and one for possession of a manufactured weapon. (An AP report posted when this information was already available offers a bizarrely sanitized version: “Friends have told local media that Rosenbaum was originally from Texas and previously lived in Arizona before moving to Wisconsin this year.”) Rosenbaum was also charged with domestic abuse and battery in July. And an infamous video minutes before he was killed shows him picking fights with the armed men and using racial slurs:

Huber, portrayed as a heroic idealist in a CNN article, had pled guilty in 2012 to felony domestic abuse involving strangulation and false imprisonment and to misdemeanor domestic abuse in 2018.

Obviously, whether Rosenbaum and Huber were nice people is irrelevant to Rittenhouse’s defense. He didn’t know about their criminal records, and even if he had known, we do not authorize armed vigilantes to hunt down and kill sex offenders or batterers. But in a case when the defendant says he acted in self-defense, the victim’s record of violence may well be relevant. And publishing a glowing tribute to the victim while omitting that record is simply not honest journalism.

Again, this is not to lionize Rittenhouse. A fatherless 17-year-old high school dropout who had been disqualified from joining the Marines and had apparently become obsessed with law enforcement had no business acting out his fantasies of being a cop by inserting himself into a volatile and dangerous situation. (Some detractors have also pointed to a video, from July 1, in which a teen who appears to be Rittenhouse is seen grabbing a teenage girl from behind and hitting her several times; while this happens in a general melee and the girl herself is seen attacking other people, this incident—if the person in the video is indeed Rittenhouse—certainly does not suggest that he has the maturity or self-control to be on an armed defense force.)

No doubt, more information will emerge on the Rittenhouse shootings in the months to come, and it will be a while before the outcome of the case is known. But for a sitting Congresswoman—Ayanna Pressley (D-MA)—to post a tweet portraying him as a “white supremacist” and a “domestic terrorist” going to Kenosha to hunt down Black Lives Matter protesters is highly irresponsible. Rittenhouse’s online activity was heavily pro-law enforcement, but so far no evidence of any white supremacist ties or sympathies has emerged. The Southern Poverty Law Center reports that Ryan Balch, a Facebook poster who has written about being part of the same armed patrol and interacting with Rittenhouse, had posted far-right and white supremacist content on a Twitter account active until December 2018; but the SPLC acknowledges that there is no indication Rittenhouse and Balch were acquainted prior to that evening in Kenosha.

Pressley’s rush to the worst conclusion may not be up there with Trump amplifying QAnon; but it shows how progressives are not always the most evidence-based either.

Black Lives Matter and the “Good Guys”

Ultimately, progressive attitudes toward violent protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement are shaped by the belief that the protests are on the right side, the rioters are simply good guys driven too far by frustration and despair, and whatever damage they may do pales in comparison to the slaughter of black people by racist forces.

But for one thing, this view ignores the fact that many of the violent protesters are genuine radicals whose motives are not identical to peaceful protesters’. Some want violent revolution. Some just want to break stuff.

For another, it ignores the fact that while too many innocent Americans—especially black Americans—are killed by the police, far more black lives are lost in places where the social order starts to collapse. This summer’s spike of violent crime in Chicago is one example. “We talk about Black Lives Matter, but I’m sick and tired of what’s going on in these streets,” Erikka Gordon, a black Chicago resident, told ABC7 recently after losing two nephews to gun violence.

Yes, police violence has its own unique awfulness, given that it comes from people entrusted with protecting citizens—particularly when it is enmeshed with America’s painful racial history. However, this should not obscure the fact that it is a far more complex problem than the racial narrative suggests. An examination of race and policing is beyond the scope of this article. But to sum it up: Racial bias and profiling play a role, apparently more in low-level police harassment and abuse than in lethal violence; there are also many other factors, and there are plenty of white people who get abused by cops or who die needlessly at the hands of the police.

In July of this year, right on the heels of the George Floyd protests, a federal judge in Dallas tossed out an excessive force lawsuit against five police officers involved in the rather similar demise of a mentally ill white man, Tony Timpa, in 2016. And ten years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a similar lawsuit by the family of a white Florida man, Donald Lewis, who died hogtied and pinned down by five cops after he was found wandering distraught and disoriented by the side of a road.

Black Lives Matter supporters such as Vox writer Jane Coaston often argue that, far from undercutting BLM’s message, widespread white victimization makes it even more urgent. Yet BLM’s core belief is that police brutality is inherently racist and expresses a “systemic” imperative to oppress, abuse, and murder black people. To “keep them in their place.”

That message may help rouse popular anger. But ultimately, it polarizes. Sarah Longwell, anti-Trump Republican consultant and publisher of The Bulwark, reports a backlash among centrist women in her focus groups. “If he was white no one would have cared,” one Arizona woman said about Blake, while others nodded in agreement.

Obviously, this is anecdotal. But even before the Kenosha events, BLM’s approval among white Americans was slipping dramatically from its high point early this summer.

It remains to be seen what impact Kenosha will have. But there is another disturbing recent trend: the protesters’ embrace of coercive tactics intended to bully non-participants into joining. A recent incident in Washington, D.C. in which outdoor diners were confronted and hectored by protesters demanding they raise their fists in solidarity with “black lives” received a fair amount of attention; but on at least two other occasions, protesters in the city have marched through residential neighborhoods late at night making loud noises to literally wake people up, and have also harassed pedestrians and drivers. Similar scenes in residential neighborhoods have taken place this month in Portland (repeatedly), in Kenosha, and in Seattle.

If this continues, the Democrats’ support for even non-violent protests could become a liability. (Ditto for the behavior of the progressive media, widely seen as part of the Democratic coalition.)

Ultimately, none of this may end up helping Trump because, despite his law-and-order posturing, he is an agent of chaos—and is widely seen as such. His reckless and confrontational rhetoric, his norm-busting, his pseudo-strongman swagger and his race-baiting have repeatedly made a bad situation worse. At least as of July, polls showed that Biden had a solid lead among voters on the question of who could do a better job on crime and safety.

But given the stakes, Democrats shouldn’t take any chances.

What Should Biden and Harris Say?

It should be said that, contrary to Trumpist insinuations, both Biden and Harris have repeatedly condemned the rioting and looting. Biden was also correct to blame and challenge Trump in his most recent statement on the subject.

This may be enough. But they could also do more.

So far, the Democratic candidates’ remarks about far-left violence have been fairly abstract. (“This is not who we are,” “Needless violence won’t heal us,” and so on.) Contrast Biden’s heartfelt comments about Blake’s shooting—“What I saw on that video makes me sick”—with his more general comments about the violence in Kenosha. (There have been some sickening moments during those riots as well, such as a video of an elderly store worker being battered and bloodied by looters.)

Biden and Harris have spoken with Blake’s family. Good. They should also speak with some store owners whose lives were shattered by violence, or with the parents of the teens killed in Seattle’s protest enclave. One or both of them should offer to meet or at least speak with Ann Dorn, the widow of the slain African-American retired police captain killed while fending off looters who gave a speech at the Republican National Convention. They should make a joint appearance to talk about the unrest, to express support for peaceful protest, to discuss the human cost of the riots and looting (it’s not simply about “property”!) and to make clear that in their America, lawlessness will not be tolerated—whether it comes from bad cops or bad protesters.

While Biden and Harris could not distance themselves from the current racial framing of police brutality even if they wanted to, they could at least partly shift the focus of the discussion from race to meaningful, ideally bipartisan police reform (such as making it easier for victims of police misconduct to sue, reducing civil forfeiture, or improving de-escalation training).

And along the way, they certainly can and should hammer Trump for his encouragement of brutality and his promotion of chaos.

Black Lives Matter helped shape the 2020 election. The movement now has its eyes on Georgia.

Founder Patrisse Cullors on the Senate runoffs, the impact of the protests, and what the movement wants from the Biden administration.

By Rachel Ramirez Nov 27, 2020, 1:00pm EST (Reprinted from Vox)

The police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor set off protests like the nation has never seen—more than 15 million people marched in the name of justice for Black lives this summer. So it’s no surprise that the rallying cry out on the streets was still on voters’ minds when they cast their ballot in November.

According to preliminary data from AP VoteCast, a comprehensive survey conducted for the Associated Press by NORC at the University of Chicago, roughly a fifth of all voters said the racial justice protests were the single most important factor when voting in the election.

But just like Americans’ views on wearing a mask or social distancing, the protests have become a politically divisive issue—53 percent of those voters went for Biden, 46 percent voted for Trump. Some conservative voters focused on the small percentage of looting and vandalism associated with the unrest, calling the protests “childish,” according to interviews conducted by the New York Times, while progressives and first-time voters were inspired by the movement to make radical change.

In the end, the Black Lives Matter movement and protests shaped the results of the election: Many organizers worked to get people out to vote, with Black voters turning out in droves, despite obstacles of voter suppression. Black voters also helped flip key battleground states like Georgia and Pennsylvania to elect Joe Biden, while voters in cities across the country approved ballot measures on police accountability.