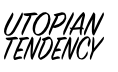

Herbert Marcuse and the Intellectual Roots of Critical Race Theory and “Woke” Ideology

by R. Tabor

November 8, 2021

Critical Race Theory can trace its origins to a body of thought known as “Critical Theory.” Critical Theory is a form of Marxism that originated in an organization known as the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research (informally, the Frankfurt School). The Frankfurt Institute emerged out of a week-long seminar in 1923, the First Marxist Workweek, whose participants consisted of mostly Jewish Marxist intellectuals. The conference was organized and financed by Felix Weil, whose father, Hermann, was a wealthy grain merchant. Through contact with the German ministry of education, in 1924 Felix was able to get the Institute formally established and officially attached to the Johann Goethe University at Frankfurt am Main, with a qualified academic, Carl Grunberg, an Austrian Marxist professor of Law, as its director. In 1930, philosopher Max Horkheimer took over the position and remained the official leader of the institute until 1958, when his close friend and collaborator, Theodor W. Adorno, became director. During the 1920s, the members of the Institute adhered to a fairly orthodox version of Marxism, but when Horkheimer took charge, he moved the group in a more creative direction.

Although Marxist theorists and members, respectively, of the Hungarian and German Communist Parties, Georgy Lukacs and Karl Korsch were involved in the First Marxist Workweek, they were excluded from the Frankfurt Institute. This occurred after the Comintern condemned Lukacs’ book History and Class Consciousness as an idealist deviation from Marxism, and Lukacs accepted the decision. Throughout its history, the Frankfurt institute did not include members of the organized Communist movement, on the grounds that party discipline would be an obstacle to independent thought.

The founding and later members of the Frankfurt Institute were deeply affected by the defeat of the German Revolution of 1918–19 and the collapse of the so-called “council republics” in Bavaria and Hungary. They were particularly concerned about the growing threat and eventual victory of Hitler and his National Socialist German Workers (Nazi) Party. In their view, the failure of the workers’ movement to stop fascism in Germany and elsewhere represented a crisis of Marxism, which the Institute’s members wished to address through a reconsideration of Marxism’s fundamental conceptions.

In the most general sense, the members of the Frankfurt School aimed to utilize Marxist categories and concepts, together with ideas derived from other intellectual trends, to develop an analysis of 20th century capitalism, especially monopoly capitalism and fascism, from a left-wing standpoint. Their work was also intended, at least implicitly, to be a critique of the versions of Marxism dominant at the time, the orthodoxies of the Second (“Socialist”) and Third (“Communist”) Internationals. Influenced originally by Lukacs’ History and Class Consciousness, by Korsch’s Marxism and Philosophy, and later by the early works of Marx, the members of the Frankfurt Institute considered the “orthodox” Marxism of Friedrich Engels and Karl Kautsky to be “positivistic” and “scientistic,” crude distortions of the real thought of Karl Marx. As they saw it, Marxism contained a philosophic dimension, apparent in the early works of Marx, particularly, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (which were only published in 1932), which Engels and Kautsky believed Marx had transcended. Among the other intellectual sources the Frankfurt School theorists utilized were late 18th/early 19th century Idealist philosophy (particularly the late works of Kant and the works of Hegel), Freudianism, the thought of sociologists Max Weber and Georg Simmel, and various forms of Existentialist philosophy. Their chief areas of interest were philosophy (including ontology, ethics, epistemology, and aesthetics), psychology/consciousness, ideology, sociology, and culture (including literature, the graphic arts, and music). Thus, the theory of the Frankfurt Institute was “critical” in (at least) three senses: (1) it was critical of contemporary capitalist society; (2) it claimed affinity with the “Critical” philosophy of Kant (particularly, the Critique of Practical Reason and the Critique of Judgment; and (3) it was critical of the official Marxism of their day, in both their Socialist and Communist embodiments.

It is essential to note that, as the theory of the Frankfurt Institute evolved, one of the fundamental tenets of virtually all the thinkers associated with the school was that the centerpiece of Marxism, the belief in the historic mission of the working class, to overthrow capitalism and establish a free, communist, society, was false. In other words, to paraphrase Friedrich Nietzsche, to the Frankfurt Institute’s theorists, the proletariat was dead. Although over the years some figures associated with the Institute were concerned to figure out exactly why this had happened — that is, what economic, social, political, cultural, and psychological mechanisms had caused the (supposed) de-revolutionisation of the working class — and although they made an effort to discern whether there were other social forces that might substitute for the proletariat as agents of revolutionary change, the “no-way-out-of-capitalism” mentality became an increasingly salient characteristic of the entire school. As a result, despite their original intentions, and despite the intellectual value of their productions, most members of the Institute became increasingly conservative as they grew older and ended up as little more than liberal (and not-so-liberal) critics of capitalism. (In fact, Horkheimer supported the US war in Vietnam as a way to prevent the Communist regime in China from dominating the world.)

Note: In light of the Frankfurt theorists’ rejection of the possibilities of a proletarian revolution and other differences with Marx and Engels’ views, I have wrestled with the question of whether they ought properly to be considered Marxists. However, since they probably continued to see themselves as such, and since today there are many leftists, both in academia and outside, who call themselves Marxists while also rejecting the possibility or advisability of a working- class revolution, I have decided to describe the Critical Theorists as Marxists.

Here is one definition of Critical Theory:

“By critical theory we mean here social theory as presented in the fundamental essays of the Zeitschrift fur Sozialfurschung (the journal of the Frankfurt Institute – RT) on the basis of dialectical philosophy and the critique of political economy.” (Herbert Marcuse, in citations to “On Hedonism,” in Negations: Essays in Critical Theory, MayFlyBooks, London, 2009, p. 217. “On Hedonism” was originally published in German in the Frankfurt Institute’s journal, Zeitschrift fur Sozial forschung Vol. VII, 1938.) In other words, to the Critical Theorists, Critical Theory is Marxism as they define it.

For his part, Horkheimer insisted that Critical Theory had to adhere to the Marxian principle of the “unity of theory and practice,” specifically, that it had to be connected to an effort to make the world a better place.

(One source I’ve read states that the term “Critical Theory,” referring to the work of members of the Frankfurt Institute, is used only in the United States.)

After Hitler was named chancellor in January 1933, the members of the Frankfurt Institute fled Germany, first to Geneva, then to Paris, and ultimately, in 1934, to the United States. There, given the dominant intellectual climate of the time, they were well received. In fact, in fact through the efforts of psychologist and Frankfurt School member Erich Fromm, the Institute was offered a home at Columbia University. During the 1930s, they produced a substantial body of work, both books and essays published in their journal. During World War II, as the Institute’s financial resources were stressed, many of its members went to work for the US government, particularly, the Central European Section of the Research and Analysis Branch of the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA. Some historians consider the Research and Analysis unit, which employed 1,200 scholars (400 of whom were overseas) to be the nursery of post-World War II American social science. After the war, many members of the Frankfurt School resumed or launched careers at major American universities. Horkheimer returned to Germany in 1949, and in 1950, the Institute was re-established in Frankfurt, Horkheimer remaining its director. While some of the school’s members also relocated to Germany, others remained in the US, where they achieved a degree of fame, along with considerable intellectual (and financial) success. Among the members of the Frankfurt Institute who became prominent, even popular, in the United States after the war were Adorno (described as a philosopher, sociologist, psychologist, musicologist, and composer), Fromm, and the philosopher Herbert Marcuse. Other theorists who were at one time or another affiliated with the Institute were Friedrich Pollock, Leo Lowenthal, Franz Borkenau, Franz Neumann, Ernst Bloch, Walter Benjamin, Karl Wittfogel, Agnes Heller, and Jurgen Habermas.

To fully understand the significance of the Frankfurt School and its influence, we need to recognize that beneath its liberatory rhetoric, Marxism, the intellectual starting point of the Critical Theorists, is an elitist, statist, and totalitarian doctrine.

Marxism’s elitism flows from its theory of truth, particularly, that there is one (absolute) Truth; that this Truth is discoverable; that Karl Marx discovered it; and that, consequently, the Marxist program and strategy, along with its theory, are the embodiments of this (absolute) Truth. More specifically, Marxists believe that Marx had scientifically discovered the True path via which humanity will be liberated, specifically, through a “proletarian socialist revolution” that will ultimately lead to a class-less and state-less society, communism. In this context, then, Marxists see Marxism as the True, Essential, consciousness of the working class, even (and especially) when the actual working class does not share this consciousness. Following from this, Marxists believe that all other philosophies, ideologies, and political programs are wrong; they are various forms of “false consciousness.” Given that Marxism posits the scientifically-discovered path to human freedom and happiness, Marxists also see Marxism as the embodiment of the Good.

Marxism’s statism flows from Marx and Engels’ conception of the state and especially its central role in the proletarian revolution. Specifically, according to Marxism, the strategic aim of the revolutionary working class is to “seize state power” and to utilize the state as the main instrument to build the revolutionary society. As they expressed it in the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels insisted that the first steps the working class must take when it revolts are: (1) to seize control of the (existing, capitalist) state and; (2) to centralize all of society’s means of production in the hands of that state. These measures, when taken, represent the establishment of what Marx and Engels called the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” Through this dictatorship, the working class would then proceed to suppress the capitalist class and its allies, shorten the work-day, and institute central planning, in so doing establishing the first phase of communist society (“socialism”), which would be based on the principle: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his work.”

Twenty-three years later, under the impact of the Paris Commune (1871), Marx and Engels partially revised this conception. They then called on the workers, when they rose up, first to smash the existing (capitalist) state and then to set up a new state, one based on the principles embodied in the Commune. This would be a state, Marx and Engels insisted, that was “no longer a state in the proper sense of the term,” and would immediately begin to “wither away.” Although they briefly considered referring to this semi-state as a “community” (gemeinschaft, in German), they eventually reverted to their previous position that it was essential that the workers establish a state, which they continued to describe as the “dictatorship of the proletariat.”

Taken together, these elitist and statist conceptions add up to a totalitarian program, specifically, the intent to use a revolutionary dictatorship, that is, a state not bound by conventional political, legal, or moral considerations (moreover, a state that has centralized in its hands all the productive resources of society), to impose the Truth and the Good (in the form of a specific social structure and an official ideology) on the rest of society. Even where the “dictatorship of the proletariat” has not (yet) been established, the elitist and statist logic of Marxism implies that Marxists ought to use the existing, capitalist, state to move toward socialism. This is the Social-Democratic, as opposed to the Leninist, variant of Marxism. Taking all this together, the logic of these central tenets of Marxism is that Marxists, the material embodiment of the consciousness of the working class, believe that they have the right and the duty to use all means — including coercive ones, up to and including a dictatorial state — to impose the Truth and the Good on the workers and all other members of society.

In the original version(s) of the theory as developed by Marx and Engels, the elitism and statism, along with the totalitarian implications of the entire conception, are partially obscured. They are hidden by Marx’s and Engels’ insistence that “the emancipation of the proletariat can only be the act of the proletariat itself,” and by their description of the dictatorship of the proletariat as the “proletariat organized as the ruling class.” Since, as Marx conceived of it, the proletariat did, or soon would, represent the majority of society, the proletarian revolution would be democratic in essence. It would be, as Marx expressed it, the “movement of the vast majority in the interests of the vast majority.” But when Marxists explicitly reject the notion of the proletarian revolution and the concomitant conception that the dictatorship of the proletariat is the “proletariat organized as the ruling class,” the elitist and statist aspects of the Marxist program become explicit, while its totalitarian implications become much easier to discern. Those Marxists who write off the working class are in fact writing off the majority of the population. The “revolution” these Marxists aim to make then becomes the act of an enlightened minority (representing the True and the Good) seeking to impose its will on the (ignorant, benighted, and unconscious) majority through the use of the state.

At times, the elitism of Marxists is expressed in striking clear (and frightening) terms:

“In critical theory, the concept of happiness has been freed from any ties with bourgeois conformism and relativism. It has become part of general, objective truth, valid for all individuals insofar as all their interests are preserved in it. Only in view of the historical possibility of general freedom is it meaningful to designate as untrue even actual, really perceived happiness in the previous and present conditions of existence….”

As a result,

“…individuals raised to be integrated into the antagonistic labor process cannot be judges of their own happiness. They have been prevented from knowing their true interest. Thus it is possible for them to designate their condition as happy and, without external compulsion, embrace the system that oppresses them.” (Herbert Marcuse, “On Hedonism,” in Negations, pp. 142-143).

This gem, whose implications I shouldn’t have to explain (“Big Brother,” anyone?), was written by one of the major representatives of the Frankfurt School, and the one who became most prominent in the United States, Herbert Marcuse, to whom we now turn.

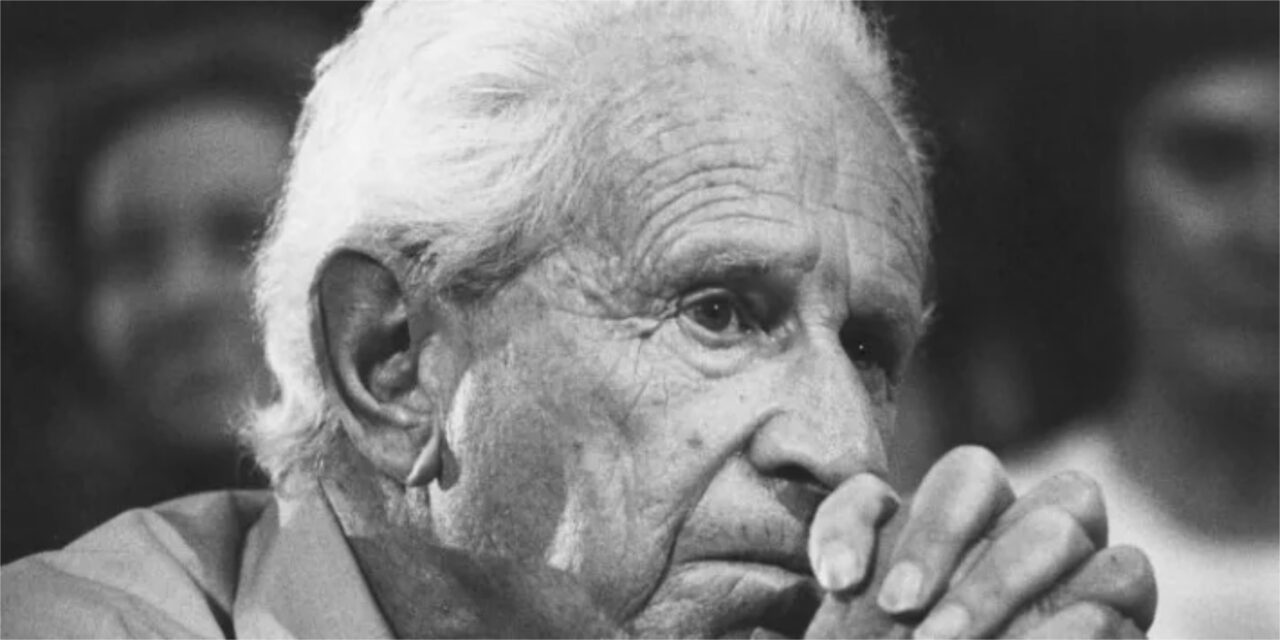

Born to and raised in a prosperous upper middle-class family in Berlin, Herbert Marcuse served in the German army during World War I; he did not engage in combat but instead took care of horses. When, after the war, workers and soldiers set up workers’ and soldiers’ councils, Marcuse, representing the SPD, was elected as a delegate to one of the soldiers’ councils in Berlin. However, he gave up his position when he learned that the councils included officers. He also resigned from the SPD after the party’s leaders, then running the government, violently suppressed the January 1919 Spartacus uprising of young workers and were implicated in the murders, at the hands of reactionary Freikorps members, of German Communist Party leaders Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, and Leo Jogisches in its aftermath.

Marcuse studied at Humboldt University of Berlin and then the University of Freiburg, eventually (in 1922) completing a dissertation on the “German artist-novel” (German novels that feature artists as main characters). He returned to Berlin, where his father got him a job working in an antiquarian bookstore. However, in 1927, the philosopher Martin Heidegger published the first part of his work, Being and Time. The book, an example of what Heidegger called “Existenzphilosophie,” had a profound impact on Marcuse and other young leftists of the time, including Karl Lowith, Hans Jonas, Hans-Georg Gadamer, and Hannah Arendt (who was then romantically involved with the married philosopher). Excited by the apparently radical turn in philosophy (very different from the tepid neo-Kantianism then dominant in Germany), Marcuse moved back to Freiburg to study with the “phenomenologist,” Edmund Husserl, and with Heidegger, and to write his habilitation (a second dissertation qualifying one to teach at the university level) under the latter’s supervision. During this time, Marcuse attempted to develop a synthesis between Marxism and Heidegger’s existentialist philosophy (which some refer to as “Heideggerian Marxism”). However, Marcuse’s dissertation, “Hegel’s Ontology and the Theory of Historicity,” was not accepted. (The circumstances surrounding this are still not clear. One scholar surmises that Heidegger first indicated to Marcuse that he would not accept the dissertation and that, in light of this, Marcuse never submitted it.) This, along with Heidegger’s sudden (and to many of his young admirers, surprising) declaration of his allegiance to the Nazis, alienated Marcuse from Heidegger. (Heidegger became chancellor of the University of Freiburg under the Nazi regime but resigned a year later and stopped attending party meetings. However, he remained a member of the party until 1945 and never publicly apologized for his pro-Nazi stance.) Shortly after Hitler seized power, Marcuse fled Germany to Geneva, where, on the recommendation of Husserl, he contacted the Frankfurt Institute. Despite some initial hesitations on the part of Horkheimer and Adorno because of Marcuse’s Heideggerian leanings, they accepted him as a colleague.

In 1934, Marcuse and other members of the Frankfurt Institute arrived in the United States. There, Marcuse worked as Horkheimer’s assistant at the Institute’s new home at Columbia University, writing regularly for the group’s journal and working on a book, Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory, which was published in 1941. The book was simultaneously a defense of Hegel (against the charge that he was nothing but a conservative and authoritarian statist), an exploration of the Hegelian roots of Marxism, and an exposition of Marcuse’s views on the role of Reason in social change.

During World War II, Marcuse first worked for the Office of War Information (essentially, writing anti-Nazi propaganda for the Allies), then, in 1943-45, in the Central European Section of the Research and Analysis Branch of the OSS. There, Marcuse joined forces with fellow Critical Theorists, Franz Neumann and Otto Kirchheimer, to produce detailed reports about various facets of the Nazi regime. When the OSS was dissolved in 1945, Marcuse moved on to the US State Department, where he studied the Soviet Union and toured Germany in an official capacity. There, Marcuse met with his former mentor, Heidegger, but Heidegger refused to repent of his collaboration with the Nazi regime. Later, after an exchange of testy letters, Marcuse broke all ties with the existentialist philosopher. (Marcuse later revealed that his initial attraction to Heidegger was based on the belief that Heidegger’s philosophy offered a “concrete-ness” that Marcuse felt was lacking in Marxism. He also indicated that he eventually realized that Heidegger’s concrete-ness was, in fact, a false, abstract, concrete-ness.) In 1951, on the death of his first wife, Marcuse resigned from the State Department and began a career in academia.

Marcuse worked first at Columbia University and then at Harvard, whose Russian Institutes sponsored his research on the Soviet Union and arranged the publication, in 1958, of his Soviet Marxism. In the words of one Marcuse scholar, the book “depicted Soviet philosophy and politics as expressions of an untenable bureaucratism, technological rationality, aesthetic realism, etc.” Marcuse insisted “that both the Soviet and Western forms of political rationality had in common the prevalence of technical over humanistic elements.” In thus equating the United States with the Soviet Union, Marcuse risked censure (and even worse) during the Cold War. (Charles Reitz, “Recalling Herbert Marcuse, Critical Theory as Radical Socialism,” in Herbert Marcuse, Transvaluation of Values and Radical Social Change, Five New Lectures, 1966-76, International Herbert Marcuse Society, Toronto, 2017, pp. 67-68).

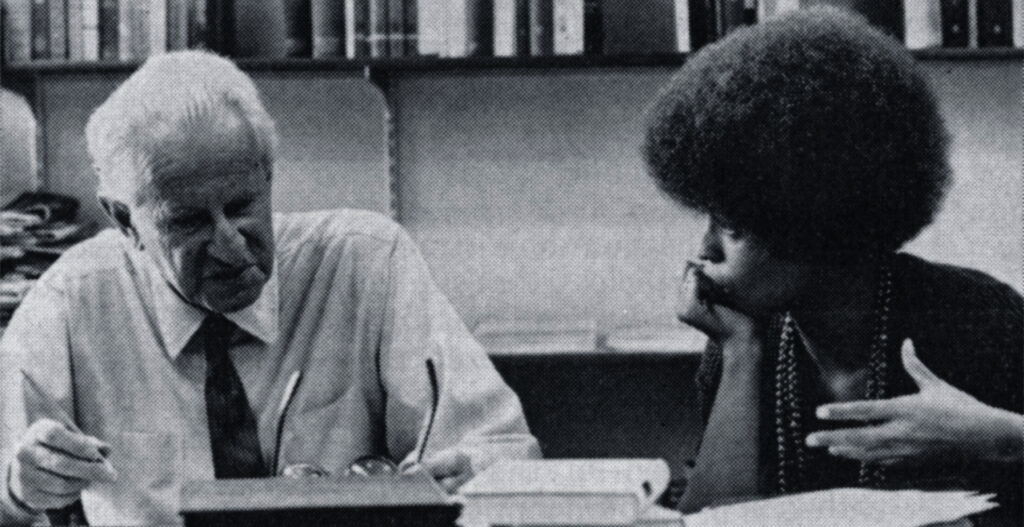

From 1954–1965, Marcuse taught at Brandeis University, where his students included Angela Davis and Abbie Hoffman. After Brandeis refused to renew his contract in 1965, Marcuse was invited to join the Philosophy Department at the University of California at San Diego, where among other activities, he supervised the master’s dissertation of Angela Davis (who had followed him there from Brandeis.) In 1968, then-Republican governor of California, Ronald Reagan, put pressure on the university to deny Marcuse a reappointment to his position, but the university resisted, extending Marcuse’s contract until he retired in 1970. During the 1960s and 70s, Marcuse was very active in the movement against the war in Vietnam and in other left-wing activities, speaking at many rallies and conferences, and lecturing on university campuses in the United States and Europe. Herbert Marcuse died of a stroke on a visit to Germany in 1979.

At some point in the late 1940s or early 1950s, Marcuse became interested in Freudianism, and most of his post-war work after Soviet Marxism involved interpretations and elaborations of that theory. This was certainly the case with one of his most important books, Eros and Civilization, which was published in 1955. While usually described as a “synthesis” of Marx and Freud, it is probably more accurate to describe it as an attempt to find in Freudianism what Marcuse felt was lacking in Marxism: specifically, a social or psychological dynamic that would guarantee (provide an ontological basis for) the liberation of humanity from capitalism. (Marx himself is never mentioned in the book.)

Marcuse saw in the human sex-drive (Freud’s “libido”) an impulse toward revolution and freedom. He based himself on Freud’s speculations about the origins of civilization in his book, Civilization and Its Discontents. Freud considered the repression of libido to be essential in making possible social cooperation and the eventual emergence, out of what he called the “primal horde,” of human civilization. But whereas Freud saw such repression, along with its corollary, sublimation (the channeling of libido into productive endeavors), as both necessary to, and inevitable under, civilization (including capitalism), Marcuse, while agreeing with much of Freud’s analysis, hoped that libido (as symbolized by Eros, the Greek god of love and sex) might be the propulsive force empowering a revolution that would free human beings from both capitalism and sexual repression. Here, Marcuse speculated about the nature of a truly liberated, non-sexually repressive society, ultimately agreeing with the German poet Friedrich Schiller that free human beings would view themselves, and life in general, in aesthetic terms, spending most of their time engaging in play.

One noteworthy aspect of Eros and Civilization is that, in it, Marcuse broached the question of whether an “educational dictatorship” (a dictatorship of a few “enlightened” individuals, as in Plato’s Republic) would be necessary to lead the repressed masses, i.e., the working class, to freedom:

“However, the question remains: how can civilization freely generate freedom, when unfreedom has become part and parcel of the mental apparatus? And if not, who is entitled to establish and enforce the objective standards?

“From Plato to Rousseau, the only honest answer is the idea of an educational dictatorship, exercised by those who are supposed to have acquired knowledge of the real Good.”

Here, in my reading (though not in others’), Marcuse rejects this idea:

“The answer has since become obsolete: knowledge of the available means for creating a humane existence for all is no longer confined to a privileged elite. The facts are all too open, and the individual consciousness would safely arrive at them if it were not methodically arrested and diverted. The distinction between rational and irrational authority, between repression and surplus repression, can be made and verified by the individuals themselves. That they cannot make this distinction now does not mean that they cannot learn to make it once they are given the opportunity to do so. Then the course of trial and error becomes a rational course in freedom.” (Marcuse, Eros and Civilization, Beacon Press, Boston, 1955, p.225.)

Later on, as we’ll see, Marcuse reconsidered the issue and came to a different conclusion.

In Eros and Civilization and in various places in his later work, Marcuse sketches, in very broad strokes, his vision of a truly liberated society. Such a society would involve a total break from the values and ethos of both capitalism and Soviet-style socialism. It would entail a complete rejection of technological rationality and the ethos of domination and control, both of human beings and of nature. It would represent the liberation of human beings from all repression, economic, social, political, and sexual. In Marcuse’s view, the creation of such a society would require a cultural and aesthetic revolution, above and beyond an economic, social, and political transformation, that would lead to the emergence of new human needs (particularly, as we have seen, aesthetic ones), far beyond those of simply securing one’s material necessities.

Marcuse’s vision, to the degree he outlined it, is maximal, radical, and (admittedly) utopian. Yet, Marcuse never answers (in fact, he never even asks) some essential questions: (1) who will manage such a society, the people as a whole or an elite? (2) will this society involve a state?; (3) will it be centralized or de-centralized?; (4) while Marcuse suggests that, in the society he envisions, exploitation will be eliminated through the institution of economic planning, who will do the planning, professionals (economists and bureaucrats) or the people themselves?; (5) will the creation of such a society require (state) coercion on the part of a minority, or will it be the act of the overwhelming majority of the people? Despite Marcuse’s failure to raise these questions, his answers to them (or at least hints about them) can be gleaned from his later works.

Marcuse’s continued interest in Freud’s ideas motivated what is probably his most popular book, One-Dimensional Man, which was published in 1964. Utilizing a combination of Marxian and Freudian concepts, Marcuse produces what is in fact a dual critique, one of post-war US society, the other of the American working class of the period. First, Marcuse analyzes and denounces what he sees as the basic characteristics of Cold War America: its nationalism and its obsession with militarism and imperialist control; its political conservatism and regimentation; its social conformity and sexual repression; its combination of alienated labor and compulsive consumption, and its superficial, commercialized, violent, and sexualized popular culture. Second, based on this analysis, Marcuse attempts to explain why the American working class (and almost everybody else in the country) remained trapped in what he calls “one-dimensional” thinking, that is, the inability to see beyond and rise above the militarist, consumerist, repressive, and conformist reality, and the ideological myths, of the country, particularly their inability to envision or entertain the possibility of an alternative, liberated society.

Marcuse sought the answer to this question in Freudian theory. Specifically, he felt that most Americans, and particularly white workers, were sexually seduced by, and addicted to, their recently acquired material possessions: their homes in the suburbs, their cars, their household appliances (e.g., washer-dryers and dishwashers), their stereos, radios, and televisions, and that this resulted in an aberrant psycho-sexual dynamic. Marcuse called it “repressive desublimation.” To Freud, we may recall, sexual repression, that is, the blockage of libido, was necessary for the establishment and maintenance of human civilization. In Freud’s scheme, however, some of the blocked libido is channeled and released, i.e., “sublimated,” into productive activities, such as work, sports, and the various forms of artistic production, while society remained sexually repressive as a whole. In Eros and Civilization, Marcuse had hoped that the power of the repressed libido would instead be the motive force that would power a popular and truly liberating revolution. But to Marcuse’s disappointment, no signs of such a revolution were to be seen anywhere on the American horizon. So Marcuse theorized that the libido was being released, that is, “desublimated,” in a manner that maintained, and even reinforced, sexually repressive capitalism. Hence, “repressive desublimation.” As a result of this dynamic, in Marcuse’s view, the revolutionary potential of the American working class leaked or dribbled out in politically harmless ways, and it was left to students and other young people, the unemployed, oppressed racial minorities, and intellectuals to resist American culture (Marcuse called it the “Great Refusal”) and to fight for progressive social goals. Moreover, Marcuse believed that the affluence of the post-war United States was permanent, that is, he thought that capitalism in North America and Europe had fully solved the problem of abundance, which Marx and Engels and later Marxists had assumed could only be achieved by socialism. As a result, in Marcuse’s view, it was extremely unlikely that the American working class would ever be revolutionary.

Indeed, by 1969, Marcuse had come to believe that the white workers in the United States were counter-revolutionary.

“By virtue of its basic position in the production process, by virtue of its numeric strength and the weight of exploitation, the working class is still the historical agent of revolution; by virtue of its sharing of the stabilizing needs of the system, it has become a conservative, even counterrevolutionary force.” (Herbert Marcuse, An Essay on Liberation, Beacon Press, Boston, 1969, p. 16.)

But one doesn’t have to resort to Marxio-Freudio mumbo-jumbo to explain why the American working class in the 1950s and 60s was politically passive and socially conservative. After nearly 25 years of economic depression and two wars (remember Korea!), the post-war boom enabled many white workers, especially those in unionized industries, to achieve a level of material prosperity that neither they nor their ancestors had ever possessed. Why should they threaten this by embarking on a struggle that might result in an economic, political, and social chaos? Moreover, what was the Left peddling at the time that might convince them to change their minds? The Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, China, North Korea, Cuba? The crushing of the Hungarian Revolution? White workers (and most other people) didn’t need Cold War propaganda to recognize how horrible those regimes were, and certainly not worth risking their hard-earned comforts to fight for.

To me, there is something profoundly elitist (and distasteful) about the attitude of Marcuse toward white workers. Like most of the figures affiliated with the Frankfurt School, Marcuse came from a wealthy family. He never had to struggle to make a living, let alone work long hours doing hard physical labor under wretched conditions in a factory, on a farm, or in a mine, let alone experience long periods of unemployment, let alone live in a noisy, crowded tenement or a tiny wooden house. Like so many leftists of the time, many of whom themselves were moving into the suburbs (and much wealthier suburbs than those the workers had access to), buying their own homes, and stocking them with labor-saving devices, stereos, and televisions, Marcuse evinces nothing but disdain for American workers for abandoning their “historic mission” of overthrowing capitalism and establishing socialism. But what if, as now seems likely (175 years after the Communist Manifesto), that “historic mission” was never a “scientifically-demonstrated” reality, but was, instead, the wishful thinking, the dream, even the delusion, of a brilliant German-Jewish philosopher?

There is something else equally or even more disturbing about Marcuse’s attitude. This is the imputation that if, at any given time, some people (in this case, white workers) disagree with him (say, about the nature of capitalism and the need for a socialist revolution), the reason cannot be a legitimate difference of opinion, but because, as Marcuse sees it, those who disagree with him are psychologically deranged. Isn’t this the real meaning of Marcuse’s analysis of white workers (and almost everybody else) in post-war America? When the workers in the 1950s and 60s in effect disagreed with Marcuse’s desired political perspective (a working-class-led socialist revolution), the only way Marcuse could account for this was by describing the workers as mentally disturbed (by “repressive desublimation”), their minds addled by their (sexual) addiction to their material possessions and a compulsion to participate in their own subjugation.

Such thinking is typical of Marxists, to whom the truth and righteousness of Marxism seem so obvious that they describe all who disagree with them as ignorant, stupid, evil, or, as in Marcuse’s case, insane. It is this thought-process that leads Marxist regimes to incarcerate political dissidents in psychiatric hospitals and “re-education” camps or to “liquidate” them as “enemies of the people.” They literally can’t believe how any rational person could possibly disagree with them. In this mentality, there are no grounds for honest differences of opinion between Marxists and non-Marxists, particularly those who, for whatever reason (among them, the actual historical outcomes of socialist revolutions and/or the belief that “planned economies” are both economically unviable and inevitably lead to bureaucratic tyranny), defend capitalism.

This attitude is especially apparent in Marcuse’s contribution to the booklet, A Critique of Pure Tolerance, written with his friends, Barrington Moore, Jr., and Robert Paul Wolff, and published in 1965. (A later edition included a postscript by Marcuse, written in 1968.) In the broadest sense, “tolerance” here refers to what Marxists describe as “bourgeois democracy,” as represented primarily by the political systems of the United States and Western Europe. More narrowly, it means the right of all political tendencies, from far left to far right, to have access to the political arena, that is, to enjoy the rights of free speech and a free press, to assemble, to public demonstrate, and to otherwise advocate peacefully for their views.

In Marcuse’s view, bourgeois democracy in the United States is a sham. On the most basic level, he believed that US society in the post-war period was “totally administered,” as totalitarian as any country suffering under a one-party dictatorship. Because of the system of controls—economic, social, political, cultural, and sexual—then in place, political freedom was, in Marcuse’s opinion, an illusion.

Marcuse’s argument proceeds on two levels. One is fairly conventional (for Marxists). Marcuse points out that the mass media, which is owned by the “rulers” (his word), controls public discourse: it is the prime source of information for society; it defines the terms of and sets the framework for public discussion; and it aggressively demarcates which views are considered legitimate in the political arena and which are not. With the capitalist-owned media so overwhelming, those who have no access to it, such as progressive and revolutionary organizations and racial minorities, are effectively marginalized. On top of this, Marcuse noted the use of the police, the criminal justice system, and prisons, along with extra-state violence (lynchings and bombings) to repress mass movements and smother dissent. (Marcuse was specifically referring to the violence directed at non-violent civil rights demonstrators in the South.)

Beyond this, Marcuse argues that the very existence of free speech (and other) rights for racist, conservative, and reactionary forces, in and of itself, marginalizes and oppresses racial and other minorities. As a result, he explicitly calls for measures to take away the political rights of such forces.

“…tolerance cannot be indiscriminate and equal with respect to the contents of expression, neither in word nor in deed; it cannot protect false words and wrong deeds which demonstrate that they contradict and counteract the possibilities of liberation….

“…society cannot be indiscriminate where the pacification of existence, where freedom and happiness themselves are at stake: here, certain things cannot be said, certain ideas cannot be expressed, certain policies cannot be proposed, certain behavior cannot be permitted without making tolerance an instrument for the continuation of servitude.” (Herbert Marcuse, “Repressive Tolerance,” in Robert Paul Wolff, Barrington Moore, Jr., Herbert Marcuse, A Critique of Pure Tolerance, Beacon Press, Boston, 1965, 1969, p. 88.)

“Surely, no government can be expected to foster its own subversion, but in a democracy such a right is invested in the people (i.e., in the majority of the people). This means that the ways should not be blocked on which a subversive majority could develop, and if they are blocked by organized repression and indoctrination, their reopening may require apparently undemocratic means. They would include the withdrawal of toleration of speech and assembly from groups and movements which promote aggressive policies, armament, chauvinism, discrimination on the ground of race and religion, or which oppose the extension of public services, social security, medical care, etc. Moreover, the restoration of freedom of thought may necessitate new and rigid restrictions on teachings and practices in the educational institutions which, by their very methods and concepts, serve to enclose the mind within the established universe of discourse and behavior – thereby precluding a priori a rational evaluation of the alternatives.” (As above, pp. 100-101.)

“Liberating tolerance, then, would mean intolerance against movements from the Right, and toleration of movements from the Left. As to the scope of this tolerance and intolerance: … it would extend to the stage of action as well as discussion and propaganda, of deed as well as of word. The traditional criterion of clear and present danger seems no longer adequate to a stage where the whole society is in the situation of the theater audience when somebody cries: ‘fire.’” (As above, p. 109.)

“The whole post-fascist period is one of clear and present danger. Consequently, true pacification requires the withdrawal of tolerance before the deed, at the stage of communication in word, print, and picture. Such extreme suspension of the right of free speech and free assembly is indeed justified only if the whole of society is in extreme danger. I maintain that our society is in such an emergency situation, and that it has become the normal state of affairs.” (As above, pp. 109-110.)

“Withdrawal of tolerance from regressive movements before they can become active; intolerance even toward thought, opinion, and word, and finally, intolerance in the opposite direction, that is, toward the self-styled conservatives, to the political Right – these anti-democratic notions respond to the actual development of the democratic society which has destroyed the basis for universal tolerance. The conditions under which tolerance can again become a liberating and humanizing force have still to be created. When tolerance mainly serves the protection and preservation of a repressive society, when it serves to neutralize opposition and to render men immune against other and better forms of life, then tolerance has been perverted. And when this perversion starts in the mind of the individual, in his consciousness, his needs, when heteronomous interests occupy him before he can experience his servitude, then the efforts to counteract his dehumanization must begin at the place of entrance, there where the false consciousness takes form (or rather: is systematically formed) – it must begin with stopping the words and images which feed this consciousness.” (As above, pp. 110-111.)

Marcuse justifies this extreme anti-libertarian (in fact, totalitarian) program on two interrelated grounds. One is the claim that the true road to human liberation can be (scientifically) discerned by rational people.

“I suggested that the distinction between true and false tolerance, between progress and regression can be made rationally on empirical grounds. The real possibilities of human freedom are relative to the attained stage of civilization. They depend on the material and intellectual resources available at the respective stage, and they are quantifiable and calculable to a high degree. So are, at the stage of advanced industrial society, the most rational ways of using these resources and distributing the social product with priority on the satisfaction of vital needs and with a minimum of toil and injustice. In other words, it is possible to define the direction in which prevailing institutions, policies, opinions would have to be changed in order to improve the chance of a peace which is not identical with cold war and a little hot war, and a satisfaction of needs which does not feed on poverty, oppression, and exploitation. Consequently, it is also possible to identify policies, opinions, movements which would promote this chance, and those which would do the opposite. Suppression of the regressive ones is a prerequisite for the strengthening of the progressive ones.” (As above, pp. 105-106.)

In other words, socialism, as Marcuse understands it (among other things, a planned economy), is obviously (and rationally demonstrated to be) the road forward for humanity.

The second justification for Marcuse’s totalitarian program is that the overwhelming majority of people in US (monopoly capitalist/imperialist) society are not, in fact, rational. As he (supposedly) demonstrated in One-Dimensional Man, the American people, including and especially white workers, are totally controlled and manipulated by the ruling class, their minds warped by a sexual addiction to their consumerist lifestyle and popular culture. The answer, in Marcuse’s view, is to find a way to liberate the minds of these unfortunate victims so that they can recognize the (Marxian) Truth.

Here is the argument:

“The question, who is qualified to make all these distinctions, definitions, identifications for society as a whole, has now one logical answer, namely everyone ‘in the majority of his faculties’ as a human being, everyone who has learned to think rationally and autonomously. The answer to Plato’s educational dictatorship is the democratic educational dictatorship of free men. John Stuart Mill’s conception of the res publica is not the opposite of Plato’s: the liberal too demands the authority of Reason not only as an intellectual but also as a political power. In Plato, rationality is confined to the small number of philosopher-kings; in Mill, every rational human being participates in the discussion and decision – but only as a rational being. Where society has entered the phase of total administration and indoctrination, this would be a small number indeed, and not necessarily that of the elected representatives of the people. The problem is not that of an educational dictatorship, but that of breaking the tyranny of public opinion and its makers in the closed society.” (As above, p. 106.)

Marcuse’s proposal for “breaking the tyranny of public opinion and its makers in the closed society” is to mold the minds of the totally administered and indoctrinated masses by attempting to limit and control which ideas they are exposed to. Hence, the proposal to suppress the ideas of the Right and to promote the ideas of the Left.

Despite what Marcuse writes, however, he has not, in fact, eliminated the need for an “educational dictatorship.” After all, the question remains: Who is to decide which ideas are to be suppressed and which ideas are to be promoted? The answer, obviously, is that Marcuse and those who think as he does will make those decisions. Although in his Postscript to “Repressive Tolerance” (written in 1968) Marcuse denies that he is calling for an educational dictatorship and insists that, instead, he is calling for struggle for democracy on the part of “revolutionary minorities,” Marcuse’s elitism (and totalitarianism) could not be more clearly expressed.

It was in the period following the publication of One-Dimensional Man and “Repressive Tolerance” that Marcuse became extremely popular among a section of the rapidly growing and radicalizing student movement, as embodied in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Pretty soon, he was being described in the media as the “guru” or the “father” of the New Left, although these were sobriquets he dismissed; he jokingly said that, at most, he might be considered the “grandfather” of the New Left. This type of hype was typical of the media at the time (and since, of course) and distorted the truth. This for two reasons.

First, Marcuse and his ideas were admired by only a section of SDS, the part that eventually evolved to become the Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM) faction(s) of the organization. Other groups within SDS definitely did not admire Marcuse’s politics. After the Progressive Labor Party (PLP) entered SDS and made it a major focus of their work, their caucus, the Worker-Student Alliance (WSA), commanded substantial and growing support within the larger organization. And PLP, which advocated a crude form (basically, “Third Period” Stalinist) of Marxism, was politically hostile to Marcuse. By the time of the split in SDS, at its convention in the summer of 1969, the PLP-led WSA commanded a majority of SDS members (at least of those who attended the convention). Yet another, much smaller, group, the Revolutionary Socialist Caucus, which opposed both the RYM and the PLP-led factions and propounded a revolutionary and democratic version of Marxism, also rejected Marcuse’s views.

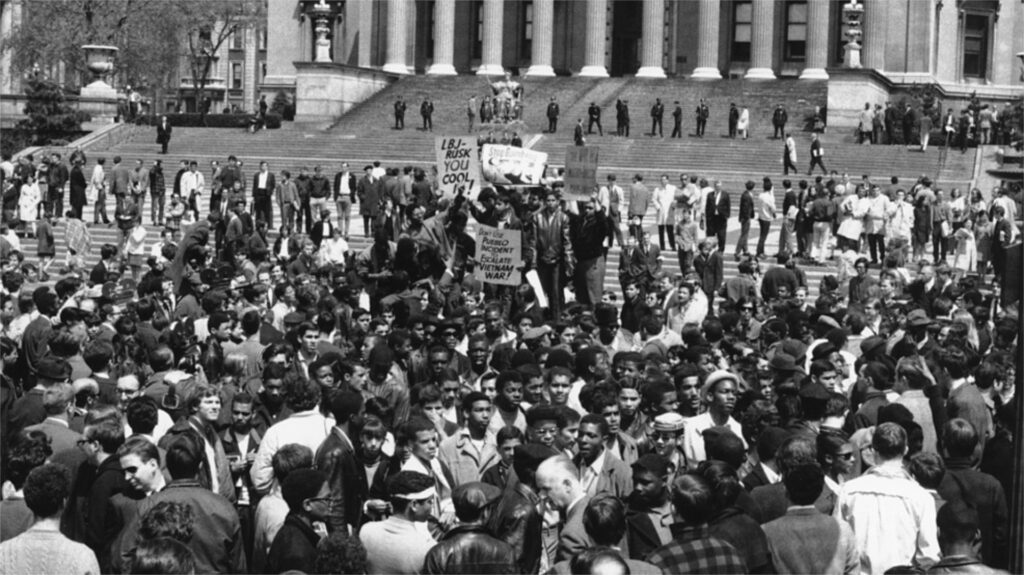

Second, while Marcuse was one of the only members of the older generation of Marxists who did not completely dismiss SDS as a bunch of “ultra-left crazies,” he also had very ambivalent feelings about the organization, particularly as it became more radical. This was revealed when in late-April 1968, on the eve of the sit-in (that was to turn into a mass student strike) at Columbia University, Marcuse arranged a private meeting with those he presumed were the leaders of the movement. There, he attempted to convince the students that they should call off the planned sit-in. Those present were shocked at Marcuse’s request, since it seemed to go against everything they thought he believed in. Marcuse attempted to explain that he was worried that the rebellious students at Columbia and at other universities might destroy the universities (and academia in general). In Marcuse’s view, this would be a disaster because the universities were the one place where multi-dimensional, critical thinking was still possible in the United States. (How convenient for him!)

(For the record, I was present at that meeting, although I was not a student at Columbia University. I attended New York’s City College, located about a mile away.)

Needless to say, the Columbia sit-in was not called off, and despite Marcuse’s fears, the universities (there and elsewhere) were not destroyed. As it turned out, the Columbia Rebellion represented the high point of the radical student movement. Students’ relative powerless to foment the social changes they desired (among them to end the war in Vietnam and to free Black people) had by then become blindingly apparent. Somewhat over a year later, SDS split apart, and the movement, in its various pieces, rapidly declined.

Marcuse’s failed attempt to get the Columbia sit-in called off reflected a reality that most of his young admirers failed to see. This was that while Marcuse’s rhetoric, the language he used in his books and lectures, along with the vision of a new society he appeared to be advocating, seemed very revolutionary, his actual politics were not. This is revealed in several ways.

Although Marcuse criticized the Soviet Union, he still considered it to be a form of socialism, albeit “bureaucratic.” Consistent with this, he had a completely uncritical attitude toward the nationalist, authoritarian, and even totalitarian leaderships of the national liberation movements that were underway that at the time. He was particularly impressed with the South Vietnamese National Liberation Front (NLF) and its patron, the North Vietnamese Communist Party. In Paris he actually met with Nguyen Than Le, North Vietnam’s chief delegate to the peace talks with the United States. Beyond his uncritical attitude toward these leaderships, he greatly overestimated the impact these movements would have on international capitalism, failing to foresee how easily the (state capitalist) regimes these movements established would be absorbed into the global capitalist system.

In similar fashion, Marcuse had deep illusions in the movements of oppressed groups in the US. He believed that the actions of marginalized racial minorities, including unemployed and “unemployable” Black people, were revolutionary even though, in his view, their consciousness was not. He had a similarly rosy view of the emerging women’s and environmental movements, believing them to have a deeply revolutionary potential and failing to see that they, too, could easily be coopted by and absorbed into the (very flexible) American political system.

Finally, by 1970 Marcuse was proposing that radical students adopt an outright reformist strategy. In his book, Counter-revolution and Revolt (published in 1972 but based on lectures delivered at Princeton University and the New School for Social Research in 1970), Marcuse urged the students:

- Not to attempt to organize white workers (in fact, not even to try to talk to them, since they – the workers – would not understand Marxist terminology);

- To give up their idolization of spontaneity and of struggles “from below,” along with their search for, and enjoyment of, alternative lifestyles;

- To abandon their hostility to liberals and instead seek an alliance, a “united front,” with them;

- To abandon their opposition to “electoral politics” (in favor of direct action) and to enter into the political system, including supporting “lesser evil” candidates in local elections;

In place of their current course, much of which he dismissed as “pubertarian,” Marcuse urged radical students to outgrow their inferiority complex about being intellectuals and, instead, to embrace their potential role as an educated, intellectual elite.

“While it is true that the people must liberate themselves from their servitude, it is also true that they must first free themselves from what has been made of them in the society in which they live. This primary liberation cannot be “spontaneous” because such spontaneity would only express the values and goals derived from the established system. Self-liberation is self-education but as such it presupposes education by others. In a society where the unequal access to knowledge and information is part of the social structure, the distinction and antagonism between the educators and those to be educated are inevitable. Those who are educated have a commitment to use their knowledge to help men and women realize and enjoy their truly human capacities. All authentic education is political education, and in a class society, political education is unthinkable without leadership, educated and tested in the theory and practice of radical opposition.” (Counterrevolution and Revolt, Beacon Press, Boston, 1972, pp. 46-47, emphasis in original.)

Based on this conception, Marcuse urged radical students to embark on what Rudi Dutschke, the leader of the German student organization, SDS, called the “long march through the institutions.” Specifically, this meant:

“working against the established institutions while working in them, but not simply by ‘boring from within,’ but rather by “doing the job,” learning (how to program and read computers, how to teach at all levels of education, how to use the mass media, how to organize production, how to recognize and eschew planned obsolescence, how to design, et cetera), and at the same time preserving one’s own consciousness in working with others.” (Counterrevolution and Revolt, p. 55.)

Marcuse’s proposed strategy was based on two considerations. One was his view of the central role to be played by the institutions of higher learning.

“I have stressed the key role which the universities play in the present period: they can still function as institutions for the training of counter-cadres. The “restructuring” for the attainment of this goal means more than decisive student participation and non-authoritarian learning. Making the university “relevant” for today and tomorrow means, instead, presenting the facts and forces that made civilization what it is today and what it could be tomorrow—and that is political education. For history indeed repeats itself; it is this repetition of domination and submission that must be halted, and halting it presupposes knowledge of its genesis and of the ways in which it is reproduced: critical thinking.” (Counterrevolution and Revolt, p. 56.)

The other consideration upon which Marcuse based his strategy was his analysis of the state of global capitalism, particularly his belief that international capitalism was in a serious crisis.

“On this long march, the militant minority has a powerful anonymous ally in the capitalist countries: the deteriorating economic-political conditions of capitalism. True, they well may be the harbinger of a fully developed fascist system, and the New Left should vigorously combat the disastrous notion that this development would accelerate the advent of socialism. The internal contradictions still make for the collapse of capitalism, but a fascist totalitarianism based on the vast resources under capitalist control may well be a stage of this collapse. It would reproduce the contradictions, but on a global scale and in a global space, in which there are still unconquered areas of domination, exploitation, and plunder. The idea of socialism loses its scientific character if its historical necessity is that of an indefinite (and doubtful) future. The objective tendencies make for socialism only to the extent to which the subjective forces struggling for socialism succeed in bending them in the direction of socialism – bending them now: today and tomorrow and the days after tomorrow…. Capitalism produces its own gravediggers—but their faces may be very different from those of the wretched of the earth, from those of misery and want.” (Counterrevolution and Revolt, pp. 56-57, emphases in original.)

I do not intend to discuss here how and why Marcuse’s analysis of global capitalism at the time he was writing was off the mark. I also do not wish to get involved in a discussion of Marcuse’s attempt (like that of so many other Marxists) to address the (glaring) contradiction between Marx and Engels insistence that their version of socialism is “scientific” (that socialism is “inevitable,” that “the (economic) base determines the superstructure,” and that “social being determines social consciousness”), and the obvious fact that the international working class has never developed the socialist consciousness that Marx and Engels predicted it would.

My main concern here is to point out (and emphasize) Marcuse’s elitism, his belief that an educated (and, in fact, middle-class) elite is the fundamental requisite for the possible socialist transformation of American society. This elitism is apparent in virtually everything Marcuse wrote and said, from the article “On Hedonism” cited above, through Eros and Civilization, One-Dimensional Man, “Repressive Tolerance,” An Essay on Liberation, Counter-revolution and Revolt, to his lectures during the 1960s and the 1970s. This elitism and its concomitant totalitarianism are fundamental, defining characteristics of his philosophy and politics.

(It is worth noting here that although Marcuse and his colleagues in the Frankfurt Institute all rejected Lenin’s conception of the revolutionary party and the October Revolution as models to be emulated, Marcuse winds up articulating essentially the same (elitist) position as Lenin (and his one-time mentor, Karl Kautsky): that the working class by its own efforts is only capable of achieving trade union consciousness; as a result, socialist consciousness must be brought to the working class “from the outside.”)

It is striking (even uncanny) how much of Marcuse’s thought and his recommendations to his student followers directly correlates with the politics and mentality of the contemporary “Woke” left:

- The (bowdlerized, i.e., neo-, quasi-, semi-, demi-, hemi-) Marxism: specifically, Marxism without a proletarian revolution;

- The hatred of white workers for their failure to carry out their “historic mission” (in fact, to live up to Marx and Engels’ predictions) and their unforgivable backwardness, including their (alleged) racism and sexism;

- The reformist (rather than revolutionary) strategy;

- The insistence on the need to ally with the liberals;

- The insistence on the need to get involved in the political system;

- The infatuation with the movements of specially oppressed groups, today known as “identity politics”;

- The elitism and the totalitarianism, the belief that Marxism embodies, and that Marxists have a monopoly of, the True and the Good;

- The belief that they have the right and the duty to repress (“cancel”) political opinions (along with the individuals who hold them, up to and including assaulting them and getting them fired from their jobs) with which they disagree;

- The willingness to utilize the authoritarian institutions of capitalism (among them, the universities, the educational system, the political system, the state in general, the mass media, and social media) to promote their program, in fact, to impose their consciousness on the supposedly benighted (and racist and sexist) masses.

Not coincidentally, there has occurred in recent years a revival of interest not only in Marxism in general, but also in the life and work of Herbert Marcuse, in particular. There now exists the International Herbert Marcuse Society, which organizes biennial conferences on university campuses in the United States and elsewhere (this year’s conference will be at Arizona State University), and which has recently sponsored the publication of Marcuse’s lectures delivered in the United States and France during the 1960s and 1970s. There is also a Herbert Marcuse Internet Archive as well as an archive of Marcuse’s letters and papers at the Archivzentrum at the University Library in Frankfurt, Germany.

Postscript

Beyond Marcuse’s writings that I have already discussed, there is his last book, The Aesthetic Dimension: Toward a Critique of Marxist Aesthetics, written in German and published in Germany in 1977, then translated and published in English in the United States in 1978 (Beacon Press, Boston). In this book, Marcuse elaborates his view of art (focusing primarily on literature, the artistic subject with which he was most familiar) and his critique of the Marxist theory of art. Marcuse’s conception of art is non-Marxist, even anti-Marxist. In his view, what he calls “authentic” art (which he never precisely defines) is totally autonomous: it cannot be explained in terms of, nor reduced to, the categories of historical materialism. Thus, while any given work (novel, short story, poem, or play) is situated in the context of the society in which a given author lived and wrote, this only provides the setting in which the work’s content exists. The content itself, and especially the meaning of the work, transcends that society, transcending, also, the specific political and philosophical views of the writer. Such content articulates what are in fact the timeless yearnings of all human beings (people throughout history) for love, beauty, truth, justice, and freedom. This explains, for example, why the works of the great tragedians of ancient Greece still “work” for us, still arouse strong emotions in us, feelings intended by the dramatists themselves. This will be true, in Marcuse’s views, under socialism. Thus, art will continue to exist even in a free, non-repressive society. For this reason, Marcuse dismisses all forms of “political” art; “socialist realism,” street theater, political posters, murals. For Marcuse, there is no such thing as “bourgeois” or “proletarian” art. Authentic art, in other words, is for the ages.

Of all the books, essays, and lectures of Marcuse that I’ve read, over the years and recently (to prepare this essay), and of all the ideas he expressed, it is only this last book, and his views on art scattered in a few pages and paragraphs in his other works, that I find to be of real, lasting value. As I see it, Marcuse’s view of art is essentially an Idealist, even a Platonic, conception, very much at odds with his Marxism.