THE UTOPIAN

Cover image from The Idiot, by Fyodor Dostoevsky

IN THIS ISSUE…

THOUGHTS EVOKED BY THE CURRENT CONJUNCTURE,

OR (WITH A BOW TO F. DOSTOEVSKY),

THE (ANARCHIST) DREAM OF A RIDICULOUS MAN

By Ron Tabor, December 10, 2022

UPHOLDING FREEDOM

My political goal at the present moment is to maintain and continue to propagate a maximal, libertarian vision of a free society. While in some sense, ideas are eternal, they do die historically, that is, they become irrelevant. (Does anybody today, aside from Christian theologians, a few philosophers, and some historians, care about Arianism and the other heresies of the early Christian church?) Today, the notion of transcending our current society—overthrowing it and replacing it with a more democratic and more just one—appears to have completely dropped out of political discourse. Even socialists and communists no longer talk about, let alone publicly advocate, revolution. Moreover, there is no guarantee that revolutionary libertarian conceptions will live on past ourselves (although I do hope that a yearning for freedom will continue to burn in enough human hearts to keep generating them). In this situation, I see my main task as attempting to keep such a dream alive.

My vision has several key components. First, the goal is the creation of a cooperative, egalitarian, and democratic—that is, a truly free, just, and self-managed—society on a global scale; no rich, no poor, no state, just people trying to live together democratically, fairly, and cooperatively. Second, such a society can be created only through a revolution, the destruction of the current economic system and the creation of a new, totally different, one. Third, as a corollary of this, such a revolution cannot be achieved by working through the existing political structures, a strategy that leaves our current socio-economic arrangements intact. This means the firm rejection of any support to (or participation in) either the Democratic or the Republican parties, or, in fact, to political parties of any kind.

The revolutionary conception I advocate does not mandate specific economic, social, or political institutions. It is not a matter of establishing nationalized, state-owned property (so-called “proletarian property forms,” in the words of the Trotskyist movement), or a state-owned and run ‘planned economy’ (as socialists and communists might describe it). Nor, in terms of the debate within the anarchist movement, is it a question of ‘communism, ‘collectivism,’ ‘communalism,’ ‘syndicalism,’ ‘mutualism,’ or “individualism.” The issue is fundamentally one of attitude, a desire to cooperate and a feeling of mutual respect and affection among a group of people. Where such an attitude does not exist, no abstract type of property or social structure or the presence of economic planning will automatically ensure cooperation. On the other hand, where a truly cooperative attitude and its associated emotions are present, the specific structures around which society is organized are also irrelevant. To put this colloquially, where there’s a will, there’s a way. Where a truly cooperative attitude obtains among a given group of people, they should be able to make almost any social form, or combination of forms, work. At one extreme, a community of small businesspeople and other individual property-owners, such as farmers, artisans, and artists, might be either competitive or cooperative, or some combination of the two. It all depends on the attitude, the feelings, of the people involved.

This position is in direct opposition to one of the central tenets of Marxism, that “social being determines social consciousness.” In my view, consciousness is, or at least can be, free. While consciousness may be, and almost always is, influenced by economic and other factors, it is not completely determined by them. People always have a choice about the attitude they take toward their lives, toward other people, toward the society they live in, and toward the social arrangement (if any) they’d like to see. If consciousness is not free, then it will be impossible to establish a truly free—democratic, egalitarian, and above all, cooperative—society. At best, all that could be created is a society of automatons or robots. Marx’s notion of a ‘leap from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom’ is absurd. If the universe is one of complete necessity (determinism), no transition, no leap, from that universe to one of freedom can occur. If a truly free society is to be possible, freedom must be ontological, that is, it must already exist, somewhere, somehow, in the universe.

We do not know (and in my opinion, cannot know) whether freedom exists as a fundamental feature of the cosmos. We therefore do not (and cannot) know whether human beings are, or can be, free. Science is of little help here; the evidence it offers is ambiguous. On the one hand, in the macro world of physics, both Newtonian and Einsteinian (Relativity), everything that happens is determined. There is no room for chance; freedom does not exist. In contrast, in the micro realm of quantum mechanics, what happens is a matter of probabilities; events are not strictly determined, and there is, seemingly, the possibility of freedom. To make matters more complicated, scientists are increasingly discovering processes that occur in the macro world but that proceed according to the laws of quantum mechanics: photosynthesis in green plants; the sense of smell of animals; and the ability of migrating birds to navigate using the Earth’s magnetic field. Even more promising, it appears that the process of evolution also occurs via quantum mechanical effects. Genetic mutations, the basis of variations within existing species that lead, under the pressure of natural selection, to the emergence of new species, are, as far as scientists have been able to discover, random. As a result, evolution is not determined. Despite this, science, at its present stage of development, does not offer a firm verdict one way or another on the existence of freedom (as opposed to determinism) in the universe and, therefore, among human beings.

As a result of this ambiguity, those of us who believe in the possibility (and the desirability) of a free society have little choice but to take the philosophical (and existential) leap to the notion that freedom does exist in the cosmos as a whole and, therefore, for human beings. Some radical theorists have suggested that establishing a free, just, and cooperative society is primarily a question of getting people to act rationally. This is essentially the argument of William Godwin, considered by some to be the father of modern anarchism. In his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, Godwin argues that if all human beings were to act in a rational manner, they would be able to live and work together completely harmoniously, without the need for a state. One problem with this conception is that it assumes that a rationality exists ontologically in the universe, independent of human beings, to which they, if they are intelligent enough, might conform, and that if they do this, the result would be a harmonious, cooperative, and just society. However, it is not at all clear that such an ontological rationality actually exists (Godwin does not even attempt to prove it). It is also not a given that, even if it does exist, human beings would be able to recognize it. Nor, finally, is there any guarantee that, even if such rationality does exist and that human beings do have the capacity to recognize it, they would all agree to act on the basis of it. As Dostoevsky illustrated in his (brilliant) Notes from Underground, there may often (always?) be people who, out of sheer perversity if nothing else, will choose to act irrationally.

In a similar vein, Jurgen Habermas, the best-known member of the second generation of “critical theorists” of the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, saw his work as promoting the creation of a ‘rational society.’ (See his books, Toward a Rational Society, and The Theory of Communicative Action.) In contrast to Godwin, Habermas conceived of such a society as arising through the gradual emergence of a process of honest and respectful communication among distinct groups of people under capitalism.

Speaking for myself, I do not wish to live in (in fact, I abhor the very idea of) a ‘rational’ society. It sounds much too much like the technocratic vision—a society governed by scientists, engineers, and businessmen—of Henri de Saint-Simon; the perfect, model communities of Robert Owen and the other ‘utopian socialists’; and the regimented ‘planned’ societies established by Marxists in Russia, Eastern Europe, China, Cuba, Vietnam, and elsewhere. Here, the crucial questions are: (1) who decides what is (and what is not) rational? And (2) do they have the power, through the state or otherwise, to enforce what they decide is rational behavior? More importantly, do we really want to live in a world in which everyone acts rationally? That sounds like one in which human emotions (which are sometimes irrational, and are usually, virtually by definition, a-rational) and the resulting spontaneity have been eliminated. (Sometimes, irrationality is good.)

In contrast to such rationalistic schemas, my dream is to live in an intelligent, but even more important, a caring society, one in which people are truly concerned about other people, about other animals, about plants, about the Earth and Nature in general, about the food we eat, the cars we drive, and the other objects we use and engage with in our daily lives. Like cooperation, this concern is not primarily a matter of the intellect; it’s not a matter of reason. It’s a question of emotions, of feelings. Today, throughout the world, most people seem to be able to care only for the beings who immediately surround them: their families, their pets, their friends, and a few of their co-workers. Universal concern, universal care, sadly, is rare. But it is what we need.

I believe that the choice of whether human beings take (or do not take) an attitude conducive to cooperation and caring is a free one; it is not, nor can it be, determined. An economically, socially, historically, or genetically determined ‘choice’ is not a choice. It’s another form of slavery, people enslaved to economics, to history, or to our genes. The decision I envision is not the inevitable outcome of the ‘laws of motion’ of capitalism, of the logic of history, or of a basic human nature, e.g., an instinct to cooperate (as in Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid). It’s certainly true that human beings have a drive to cooperate. But they also have a drive to compete, which is why, up to now, most human societies (all that I know of, at least) have been based on various combinations of cooperation and competition. In fact, human beings have cooperated in one form or another throughout our history, but such cooperation has always occurred within broader competitive situations. Even contemporary capitalism, which some see as the epitome of a competitive, dog-eat-dog, society, entails cooperation within its overall hierarchical and competitive structures. The crucial question now is whether human beings are capable of rising to a higher level of cooperation, one that is both broader (that is, embraces wider groups of people) and deeper (that is, entails more intense social concern), than what is evinced under our current social system. And whether this actually occurs will involve the free choice of the individual members of the human species. Although some may object to my use of words, I see this decision, this leap, as entailing a spiritual revolution on a global scale.

Beyond being based on a free choice, the social transformation I imagine must be the result of the more or less simultaneous decisions and actions of the overwhelming majority of people in the world. It cannot be the outcome of a minority attempting to impose its will on the majority. It cannot be the action of a technical majority (50% + 1) that forces its conception, even via ‘democratic’ structures, on everybody else. And it cannot be carried out through the action of a state (the ultimate institution of coercion), even (or especially) if that state calls itself the “dictatorship of the proletariat” and promises to ‘wither away’ when its services are no longer needed. Unless there emerges a virtual consensus among human beings in a relatively short period of time, any revolution that takes place will merely result in the re-establishment of our current form of society, or something worse.

Equally important, the revolution I envision cannot be a violent one, certainly not like the majority of the revolutions that have occurred throughout history, nor those that have been carried out, and idolized, by the left. Such violent overturns, whatever their specific results, almost always bring out the worst in people: resentment, fear, greed, and hatred; xenophobia, racism, and sexism; fanaticism; and the resulting brutality and cruelty. Insofar as there are events that have occurred in recent history that might be a model for my conception of a revolution, they are the movements that destroyed the Communist regimes in Eastern Europe in 1989. From everything I’ve been able to determine, these overturns involved, or at least were supported by, the overwhelming majority of people in those countries. Largely because of this, they entailed extremely little violence. Unfortunately, given the experience of people under Soviet rule, to them, anything, even Western-style bourgeois-democratic (and not-so-democratic) capitalism, was better than Communism. Not surprisingly, then, this was the outcome of those movements. What I would like to see are revolutions like those, but which result in truly democratic, egalitarian, cooperative, and above all, caring societies.

In my view, this would require the evolution of the human species to a higher moral and ethical level than it has attained so far. I believe that the existing global economic and social system—capitalism—represents the evolutionary stage at which human beings have arrived. In other words, capitalism is the embodiment of contemporary (evolutionarily produced) human nature. This explains why the various attempts in the 20th century to create societies that are ‘higher,’ more ‘progressive,’ more just and cooperative, than capitalism—e.g., the Russian Revolution, the Chinese, Cuban, Vietnamese, and Nicaraguan revolutions, to name a few—have failed. Looked at the other way around, had the overwhelming majority of people in any of these countries really wanted to live in a new (democratic, egalitarian, and cooperative) way, what forces could possibly have stopped them? In these places, dictatorships were resorted to, and viciously maintained, precisely because the majority of the people did not, ultimately, agree with the rationalistic, totalitarian goals of their would-be leaders.

Perhaps the most striking demonstration of the moral immaturity of humanity today is the plight of homeless people in Western European and North American societies. Here, the elimination of homelessness is not a question of a lack of resources, as it might be in developing countries. Nor is it one of a dearth of ideas; surely, a bunch of people, a committee or a commission that included homeless people, ought to be able to come up with a way to get unhoused individuals and families into decent, clean, and warm homes (however modest), where they might live in some degree of comfort, privacy, and freedom, instead of leaving them to struggle to survive on the street. That our modern economically-developed societies have not solved, or even tried to solve, this dire social issue – not to speak of the efforts of some people, even whole communities, to force homeless people out of their neighborhoods (Anyplace but here!)—reveals, to my mind, the moral/ethical inadequacies (to put it euphemistically) of contemporary human beings.

Embracing Humanity

If the social transformation I envision is to occur, it must, as I discussed above, involve the overwhelming majority of people, first, in a given society, then, in the world. This means that those of us who wish to promote such a revolution must aim to reach people who have traditionally been excluded from the strategic conceptions of the left.

First, we must seek to include small and medium-sized property owners—entrepreneurs, factory owners, shopkeepers, restaurant owners, farmers, artisans, and artists—in our vision. Contrary to much left-wing theory, such people are not inevitable supporters of right-wing or fascist movements. Their consciousness is not automatically determined by their economic circumstances; they are not all money-grubbing, selfish boors. As in all other strata of society, the people involved in these enterprises encompass the full range of human personalities, with all their values, virtues and vices. Among other things, this means that revolutionaries should not see their goal as the expropriation of all property, from the largest to the smallest, and its nationalization by the state. Small businesses, in all their forms, are an essential part of the modern economy, carrying out many functions that large enterprises can’t or won’t do, or can’t do well. They also employ and serve a huge numbers of people and are responsible for a great deal of technological innovation. (It is worth recalling that personal computers were not invented by IBM and the other tech giants of the day, but by independent inventors, working in their garages.)

Second, the movement needs to reach out to, appeal to, and embrace religious people. Not all religious individuals are inevitably hostile to the vision we advocate. There are billions of people in the world today who believe in God. These people should not automatically be written off as ignorant, deluded, and stupid, inveterate enemies of our goal. Among other things, this means that we should reject all forms of what I call ‘militant atheism,’ that is, efforts to proselytize atheism among believers, to convince them that their religious beliefs are wrong—unscientific, foolish, and stupid—and that they must reject their faith in God and instead embrace the one and only true and scientific belief, atheism.

It is certainly understandable why early radical and revolutionary movements rejected religion. The established churches unabashedly placed themselves on the side of the existing societies (in fact, usually allying with their most reactionary elements), justifying their cruelty and injustices, defending their elites, and damning all efforts to reform them, let alone overthrow them, as contrary to the will of God. But, after two centuries, it ought to be clear that such a position has been and is completely counterproductive. While many intellectuals are attracted to and adopt abstract ideologies and philosophies, most people, and particularly working-class people, tend to think in more graphic and symbolic terms. They also appreciate religious celebrations, rituals, and rites that they enjoy and that help them to organize their lives, involve them in a community, and offer a sense of meaning to their existence. Philosophically, it is worth noting that it is just as impossible to prove that God does not exist as it is to prove that He (She, It, They) does exist. It is also not true that science provides any proof of or justification for atheism. Contrary to the claims of such militant atheists as Richard Dawkins, science does not promote, nor does it provide any support to, atheism; it is strictly neutral on the question of the existence or non-existence of God. Science merely insists that, in their public discussions and debates, scientists deal with, and argue in terms of, exclusively empirical, testable, natural phenomena. It takes no stance on religious issues, neither on the personal views of individual scientists, nor on how they reach their scientific conclusions. In fact, many of the world’s most important scientists were religious: Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Newton, Mendel, Le Maître, and Einstein. These individuals, and other like them, explicitly saw themselves as attempting to discover the logical structure of Nature, God’s wonderful Creation. Most important for our concerns is that there are millions of kind, caring, thoughtful, and socially concerned individuals who are religious. And while some religious people are fanatic and intolerant, many non- believers (atheists) are equally so. (The international Communist movement, with its ideological commitment to militant atheism backed up by totalitarian states, did not set an admirable example of tolerance and broadmindedness in this regard.) To condemn religious people for their beliefs is to attack the very core of their being; it is also rude and insulting. Above all, it is elitist. Militant atheism is the philosophy of a would-be intellectual and moral elite that sees its role as bringing the Truth to an ignorant and deluded (and ultimately stupid) mass of common people, as replacing the ‘false consciousness’ (in Marx’s phrase) of the reactionary petty bourgeoisie with the true, supposedly scientific, consciousness of the ‘revolutionary proletariat.’ It is also worth noting that the various visions of socialist and anarchist thinkers of a free and just society in fact have their sources in the apocalyptic visions of Christianity, even though the originators and current proponents of these views have often been too obtuse, or too blinded by anti-clerical rage, to recognize this.

Third, the proponents of the kind of revolution I imagine must reach out to conservatives, including supporters and members of the Republican Party. Contrary to the views of most of the left, not all conservatives, even those who voted for Donald Trump, are racist bigots, heterosexual chauvinists, Christian nationalists, and fascists. Nor are they all stupid, ignorant, and selfish. In contemporary US society, there are plenty of reasons why intelligent, informed, and socially-concerned people might consider themselves to be conservative and vote for and otherwise support the Republican Party. On the most human level, many people vote for the party because that’s the way their family has always voted and/or because it is how their friends and the surrounding community vote. In addition, many of the positive values that human beings share are seen by right-leaning people as ‘conservative,’ specifically, hard work, thrift, common decency, self-discipline, independence, personal responsibility, charity, and honesty. It is also worth recognizing that many people who support the Republicans are (rightly, in my opinion) repulsed by the politics and actions of the left- wing of the Democratic Party, particularly their strategy of attempting to force their views on everybody else through various kinds of coercion, including that of the state. This can be seen quite clearly in the gratuitous violence (the systematic trashing of small businesses), the thorough-going dishonesty, and the putrid venality of the leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement; the thoughtless cruelty of ‘Cancel Culture’ (specifically, getting people who disagree with the left’s positions fired from their jobs); the attempts, under the guise of fighting racism, to impose Marcusian Marxism on students, parents, and teachers through the public schools; and the totalitarian thuggery (shouting down or banning speakers who articulate unpopular views) currently rampaging across many, if not most, college campuses today.

The Left

My conception of a revolutionary libertarian transformation of society requires the firm rejection, and ultimately, the complete transcendence of the contemporary left. The problems with today’s left are many. One is its reformism. Today, the most prominent and influential groups on the US left, the Democratic Socialists of American (DSA) and the Communist Party (CPUSA), pursue purely reformist strategies. They have entirely given up any notion of advocating, promoting, or leading a social revolution. This is most clearly revealed in the fact that the strategic orientations of these groups, along with many independent ‘progressives,’ come down to supporting—voting for, organizing for, giving money to, and being active in—the Democratic Party, the hegemonic party of contemporary US capitalism.

Equally important, the vision of these leftist and progressive organizations and individuals is profoundly statist. Their goal is to set up a society in which the state/government has taken over much, most, or even all of the economy, which would, in their view, be managed through central (bureaucratic) planning. They call this ‘socialism.’ The more precise aim of the majority of the left today is to push the US government to implement a modern version of FDR’s New Deal, even though the New Deal (as was the Progressive program before it) was consciously designed to offer a pro- capitalist alternative to the socialist program of the Communist Party and (it’s worth remembering) the Socialist Party. Even the few groups that still advocate revolution (mostly groups that come out of the Trotskyist tradition) see their goal as establishing a thorough-going—that is, statist— form of socialism. It should be obvious by now that, whatever its origins, the ‘socialism’ advocated by the left today is really a form of ‘state capitalism,’ that is, an industrialized society managed by a bureaucratic elite through an omnipotent state.

Although many of today’s socialists insist that their real goal is to establish ‘democratic socialism,’ there are (at least) two reasons to doubt the validity of such claims. First, many if not most of these proponents of ‘democratic socialism’ were, for many years, militant supporters and defenders of the not-very-democratic socialisms that existed in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, China, Vietnam, Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. Second, ‘democratic socialism’ is, in fact, a contradiction in terms. This is because if the government (run by bureaucrats) of a given country owns all the property, how can the people defend themselves against the government, let alone control it, when, completely stripped of any economic resources, they lack the power to do so? This is one thing that the various socialist revolutions of the 20th century have clearly demonstrated.

Despite the fact that the contemporary anarchist movement traces its origins to different sources than the CP, the DSA, and other ‘progressives,’ it advocates many of the same positions. Although the movement’s official vision is anti-statist, it, too, finds itself in (and advocates) a bloc with the Democrats. Thus, many anarchists openly urge support of (specifically, voting for) the Democratic Party. Many also accept the continued existence of the capitalist system, only working to build ‘alternative’ communities and promote ‘alternative’ practices within it. And many anarchists conceive of their role as fighters for the radical, even the revolutionary extension, of Identity Politics. Yet these politics, as revealed by the corporate elite’s ready (even aggressive) adoption of them, represent absolutely no threat to the system. This is because such politics: (1) set each of the (oppressed) identity groups against all the others; (2) set the identity groups as a whole against their supposed oppressors: heterosexual white men, white people in general, and even ‘white-ness’ as a concept; and thus (3) set the majority of people against one another, turning their hostility inward instead of uniting them in a common struggle against the real oppressors, the country’s ruling class. Ironically, identity politics, despite the good intentions of its proponents, dovetail with, and even reinforce, that most fundamental tactic of elites throughout history: Divide and Rule!

Although it sees itself as revolutionary, the most militant wing of the anarchist movement, Antifa, has reduced itself to being little more than paramilitary shock troops of the capitalist elite. Deluded into believing that it is on the front lines of the fight against fascism, it is merely helping to restore the elite’s (Democratic and Republican alike) control over the political system against a rogue member of that elite, Donald Trump, who, through a series of mistakes on the part of the rest of the elite, temporarily hijacked the system.

Marxism

Probably the most significant problem with the left today is that all of its components, including the anarchists, are committed (a better word might be ‘addicted’) to various forms of Marxism. Yet, it should be obvious today that Marxism is ridiculous. Here we are, 175 years since the publication of the Communist Manifesto, and the supposedly scientific predictions that Marxism proffers have clearly revealed themselves to be wrong. There has been no international socialist revolution through which the working class would liberate itself and all of humanity from the evils of capitalism. The Communist regimes that were established by Marxists in the 20th century turned out to be totalitarian monstrosities that slaughtered tens of millions of people; exiled, imprisoned, tortured, starved, and worked to death millions of others; attempted to suppress all independent thought and culture; and devastated environments across a good portion of the globe. Not least, these regimes proved incapable of competing with traditional capitalism on any significant level, e.g., raising productivity, promoting economic growth, producing quality consumer goods, improving the living standards and the quality of life of the majority of people, and generating new technology.

Contrary to Marxism and state-socialist ideologies in general, state-owned and state-managed property is not superior to private enterprise. This has been decisively demonstrated by the one Communist society that has thrived in the current era, that of China. The Chinese economy has been dynamic only to the degree that it has, as an imitation of the New Economic Policy introduced in Russia after the civil war had resulted in the complete destruction of the economy, allowed its free-market sector a virtually free hand, that is, cultivated a private, capitalist economy while retaining tight political (and ideological) control over the country.

Because of its commitment to Marxism, the left has consistently underestimated the resilience of the capitalist system. Going back to the earliest Marxist declarations, the world’s people (particularly, the international working class) have been told that if they/we do not succeed in establishing socialism, the outcome will be one or another form of global catastrophe. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels imply that if socialism is not achieved, the result will be the ‘common ruin of the contending classes,’ presumably (in reference to the collapse of the western half of the Roman Empire under the impact of invading Germanic tribes), a form of ‘barbarism.’ Later, just before the First World War, Rosa Luxemburg, the left-wing gadfly of the German Social Democratic Party, made this explicit, boldly raising the slogan of ‘Socialism or Barbarism!’

Since then, spokespersons of the left have claimed, loudly and repeatedly, that if capitalism is not overthrown and socialism established, the (inevitable) result will be a global economic depression, fascism, nuclear annihilation, and most recently, climate change disaster. And yet, here we are. While we have experienced two world wars (and many smaller wars), two serious global economic contractions, fascist regimes in many countries, and have skirted the edge of nuclear war, somehow, the international capitalist economic system (and the human species with it) has survived. Equally important, contrary to the predictions of many leftists, global capitalism is now undergoing a transition away from an economy based on fossil fuels towards one that is overwhelmingly based on ‘green,’ renewable energy. Should this transition have begun decades ago? Absolutely! Has the delay in launching the transition done great harm to the global environment and to many countries and peoples around the world? Certainly! Will we continue to see damage to the environment? Yes! But somehow, some way, and in complete confutation of the predictions of the left, the global transition to a green economy is, in fact, taking place (and, I believe, will succeed).

Finally, and probably most important, there is absolutely no sign today of the existence (or even the potential emergence), of a ‘revolutionary proletariat,’ the militant, organized, politically conscious, and revolutionary working class that recognizes its (ontologically ordained) role of overthrowing capitalism and establishing socialism, which Marx predicted would be the inevitable outcome of the internal dynamics (the “laws of motion”) of capitalism and, in fact, all of history. Sociologically, a global proletariat does exist, but it shows no sign of having any clue to its Marxist- proclaimed emancipatory role.

Beyond being wrong, Marxism is dangerous:

- Through its claim to have scientifically proven the ‘necessity’ and ‘inevitability’ of socialism, it instills in Marxists the conviction that they are the personal and political possessors, even the embodiment, of the Truth, the Good (the Liberation of Humanity), and History.

- It instructs Marxists that the only way to realize their goal (the liberation of humanity) is to set up a revolutionary dictatorship that recognizes absolutely no limits to its authority, respects no conventional moral/ethical laws, rules, or values, and which has seized and consolidated all property in its hands.

This is a recipe for totalitarianism, which is, in fact, what Marxism has historically produced.

The Ukraine War

The bankruptcy of the left today is vividly revealed in its virtually complete failure to support the struggle of the Ukrainian people against Vladimir Putin’s invasion of their country, against his attempt to deny them their right to national independence and self-determination, and his determination to deny their very right to exist as a people. The right of national self-determination is one of the most fundamental of human rights. And yet, the majority of the left, which prides itself on its defense of such rights, has not managed to come down, forthrightly and squarely, in support of this right for the Ukrainians, a people which has been struggling to define themselves as a nation and to fight for their freedom for nearly 200 years. Instead, most left organizations have come up with a bunch of lame excuses for their refusal to support the Ukrainians in their life-and-death struggle. Perhaps even worse, because more devious, many left organizations have been hiding their pusillanimity under the slogan of “peace,” attempting to pressure the Ukrainians to negotiate with Putin in order to ‘avoid more bloodshed.’ But at this point in the war, when the Ukrainian people are clearly winning, such calls for peace are a stab in the Ukrainians’ collective back, a betrayal of their extraordinary struggle against overwhelming odds.

At best, the failure of the majority of the left to defend the Ukrainians in their struggle for national survival is motivated by a well-intentioned but thoughtless anti-imperialism. (US imperialism is bad, therefore all who resist it, including and especially the Russians, are good.) But while opposing US imperialism, the left has become little more than supporters of the historic imperialism of the Russian autocratic state, accurately described as the ‘prison house of nations,’ of which Putin’s regime is the latest embodiment. In many cases, the left’s failure in the Ukraine war is a reflection of a deep-seated authoritarianism that exists in left-wing theory and ideology and that often results in an attraction to and infatuation with charismatic dictators, such as Vladimir Putin, V. I. Lenin, Yosef Stalin, Mao Zedong, Ho Chi Minh, Fidel Castro, Hugo Chavez, and Daniel Ortega. It is also, it must be said, the result of the moral corruption of much of the left, its willingness to accept, and even to rely on, Putin’s financial largesse, his substantial monetary subsidization, direct and indirect, of many left-wing organizations and individuals in the United States and around the world. (How many prominent figures of the US and international left have worked for Putin’s propaganda outlets, such as RT [Russian Television], or have been feted at one or another of Putin’s banquets—Stephen Cohen, Chris Hedges, and Jill Stein, to name only a few?

The Democratic Party

As I mentioned above, a combination of the left’s reformism and statism (and its theoretical bankruptcy) has turned the overwhelming majority of today’s leftists into militant supporters of the liberal wing of the capitalist class, politically led by the Democratic Party. This stance is usually motivated by the claim that the Democrats are the “lesser evil” compared to the conservative (‘reactionary,’ or even ‘fascist’) Republican Party. Yet, this is to seriously misunderstand the nature of the Democratic Party and, more broadly, the American two-party system, of which the Democrats, along with the Republicans, are a fundamental part, and to which they are both militantly committed.

Today, the Democratic Party is, and has been for the last thirty years, the hegemonic party of American capitalism. It is supported by the majority of the American electorate and by a majority of our country’s economic and political elite. Since 1992, the Democrats have won, outright, five of the eight presidential elections that have been held since then: 1992, 1996, 2008, 2012, and 2020. In two other elections, those of 2000 and 2016, the Democrats won majorities of the popular vote, but, because of the quirks of the US political system (and poorly run political campaigns), they did not win majorities in the Electoral College and thus did not attain the presidency. If we count these two elections together with those in which the Democrats did win the presidency, the total of Democratic victories since 1992 comes to seven (out of a total of eight).

Looked at more broadly, the Democrats’ political hegemony goes back ninety years, specifically, to 1932, when Franklin D. Roosevelt clobbered the previous, Republican, president, Herbert Hoover, in the election of that year. Since then, the Democrats have won the presidency 13 times compared to the Republicans’ ten. Equally important, during the two Eisenhower/Nixon administrations and the two Nixon/Ford administrations, the Republicans basically pursued the Keynesian policies (deficit spending and social welfare programs) that were pioneered by the Roosevelt administration and continued by Truman’s. Seen in this light, the Democrats and their policies, that is, their overall approach to governing the country, have been overwhelmingly dominant in the United States for nearly a century.

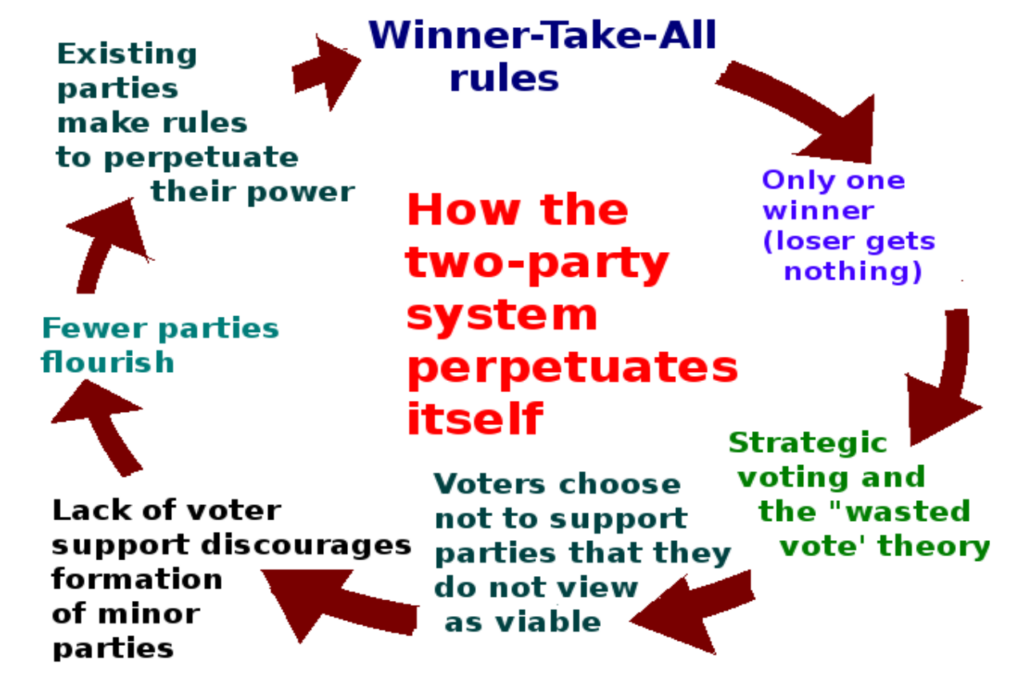

To fully understand the Democrats’ (hegemonic) role, one must understand the nature of the American two-party political system. Although a two- party structure is not explicitly mandated by the US constitution (nor, as far as I know, specifically envisioned by the ‘Framers’), it is the logical result of that document. Without going into details, it is worth noting several features of the United States’ historic political arrangements that conduce toward a system organized around two major parties. First, the US political system is a “presidential” one, in which voters vote for and elect the president directly. This is in contrast to a ‘parliamentary’ one, in which voters vote for specific political parties, and the party (or the coalition of parties) that wins a majority or a plurality of the votes (more votes than any other party or combination of parties), then chooses one of its (their) leaders to head the government. Second, the American system is a ‘winner take all’ system; only one party wins in contests for specific elected positions; the losing party gains nothing, and there is no proportional representation. Third, because the Unites States is a federation, any would-be party must, to be a serious national contender, get on the ballot in all 50 states, a time-consuming, tedious, and expensive process. As a result of these and other factors, throughout most of the country’s history, its politics have been dominated by two major parties, each of which embraces and (more or less represents) a broad coalition of interest groups and voters. In general, those groups and voters who find themselves consistently in a minority feel pressed to join together in the hope that they might, at some point in the future, become the majority. As a result, there has been a tendency for the third parties that do emerge either to (relatively quickly) replace one of the previously dominant parties (as the Republicans replaced the Whigs in the course of the 1850s) or to (also rather quickly) collapse into the one of those parties, as the Populist Party merged into the Democratic Party in the late 19th century and the post-World War II Progressive Party collapsed into the Democratic Party after the 1948 election.

However the two-party system emerged and for whatever reason it has survived, it has, functioning within the framework of the US constitution, served the ruling class very well throughout its history. Today, we can see some of the reasons why. Perhaps most important, the two-party structure tends to divide the electorate roughly in half, that is, into two more or less equal pieces, each of which sees the other as the enemy. This means that it is very difficult for the electorate as a whole to unite in a common struggle against the elite, to recognize that it has common interests against that elite, or even to recognize that there is an elite. It also provides for a flexible, but ultimately strong and resilient, structure within which and through which the various economic and political factions of the elite fight out their differences, usually without threatening the overall structure of US society.

The two-party structure works to stabilize the broader economic and political system in other ways. This is perhaps most easily seen on the economic plane. Since the 1930s, the two parties have advocated two competing economic philosophies. The Democrats, on the whole, have stood on the platform of Keynesianism, first developed and applied by the Roosevelt administration in the 1930s. Economist John Maynard Keynes recognized that the mature capitalist economy has a tendency to stagnate. In his view, this is because as people get wealthier as a result of economic growth, they tend to spend proportionately less of their income and save more, leading to a relative decline in ‘effective demand.’ To solve this, he urged central governments to bolster demand through government spending of funds raised by borrowing money via the sale of government bonds (so-called ‘deficit spending’) to the public. Consistent with this, the Democrats also believe that the system functions best when the government, particularly but not exclusively the federal government, intervenes in the economy to promote consumption, flatten the business cycle, and address broader economic and social issues, such as poverty, inequality, and the environment. This has tended, over time, to mean large budget deficits (and growing public debt), increased regulation of business, a variety of government-financed and operated social programs, and to pay for this, higher taxes on both private businesses and individuals.

Although for 25 years after World War II, the Republicans embraced the Keynesian approach, they were never happy about this. As a result, when the US economy experienced ‘stagflation’ (a combination of economic stagnation and inflation) in the 1970s, the result, in their (and my) opinion, of 40 years of Keynesian policies, they reverted to their traditional position: that the capitalist economy functions best when the market generally, and individual enterprises specifically, are allowed to operate freely. This means lower taxes, fewer regulations of business, less government spending, and fewer federally-funded social programs to deal with social issues (which the Republicans argue are best addressed by promoting economic growth).

It seems clear today that the modern capitalist economy functions best with some degree of government intervention, although it is not clear exactly how much of such intervention is optimal. Too little results in the ‘boom-bust’ cycle characteristic of 19th century capitalism and which led, ultimately, to the global Depression of the 1930s. On the other hand, too much government intervention leads to economic stagnation. (An extreme example of this is the state-owned and managed economy of the Soviet Union in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, where anemic economic growth ultimately led to the collapse of the entire system.) Since economists do not agree on this issue, and since, in any case, the optimal amount of government intervention is not theoretically discernible, the question is addressed, de facto, through the political system, specifically, through the alternation of the two—Democratic and Republican—political parties in power. When, for whatever reason, the voters (and the elite) are unhappy with the way the economy is functioning, they vote out one party and vote in the other. This results in the periodic alternation of the two economic philosophies described above. In this way, through the workings of the two-party system, the US economy tends to reach a long-term equilibrium, specifically, an oscillation around its optimal state. This is, in my opinion, one of the reasons why the US economy has been able to maintain a reasonably healthy rate of growth for so long, at least since the 1930s, and why the United States has maintained its global economic and political hegemony, despite being challenged by one or another country (Russia, Japan, China) in the past.

The two-party system works in a similar manner on the political level. The overall arrangement tends to force the political extremes toward the center. This is because that’s where political power lies. Under the US political system, small parties in general don’t get elected; indeed, they can hardly get their voices heard. As a result, people with unconventional—that is, far-left or far-right—views have a better chance at least to get heard, if not to have some genuine input (and even power), as part of the large coalitions that are the two main parties. This explains why the vast majority of the left, both organizations and individuals, is active in, contributes money to, and/or otherwise supports and votes for the Democrats. A similar phenomenon exists on the right side of the political spectrum: the overwhelming majority of the far-right operates within, supports and votes for, the Republicans. Generally speaking, the power of the extremes—that is, the left in the Democratic Party and the right in the Republican Party—is minimized because the vast majority of the elite (as represented politically in the respective Democratic and Republican ‘establishments’), which ultimately control the two parties, and a similar majority of the people who vote in elections, are centrists. However, this dynamic can only be sustained if the two parties actually alternate in power. If one party were to win all the time, the outlying voices and forces would seek their fortunes and take their chances outside the two main parties. For example, if the Democrats always won (and the Republicans always lost, and are seen as having no chance to gain power) why would far-right organizations stay in, support, and vote for the Republicans? If there is absolutely no chance of gaining power, or at least getting close to it, why stay in the Republican Party? Why not just form right-wing organizations and parties outside the Republican Party and do what one can to get one’s voice heard and program known? Likewise on the Democratic side. If the Democratic Party always lost, why would leftists remain in the party? It’s the potential access to power, or at least to influence, that keeps the supporters of the political extremes inside the two major parties, and hence working within the system, rather than outside of it and threatening its stability.

Here we can see what is faulty in the view that the Democrats are the ‘lesser evil’ for whom, at the very least, liberals and leftists should vote, to whom, at a higher level, they should contribute money, and in which, for the most committed, they should be active. For if the Democratic Party won every election, all posts on all levels—local, state, and federal—(which is, after all, the de facto goal of people who consider the Democrats to be the ‘lesser evil’), the results would be:

- The country’s economy would stagnate, as it did in the 1970s.

- Because of this, federally-managed and funded social programs would not be affordable and would not be adequately funded; they would therefore shrink and possibly collapse altogether.

- A mass far-right, fascist, and Nazi movement would emerge outside of the Republican Party, able to appeal to, and organize, the huge numbers of people in the country who are alienated from and deeply hostile to the Democratic Party and the (hegemonic liberal (greedy, arrogant and hypocritical) faction of the elite that it represents.

Consequently, liberals and leftists, who hate the Republican Party and see it as a fascist organization, really ought to be thankful for it, since it, in tandem with the Democratic Party, actually works to prevent the emergence of a mass fascist movement in the country.

As a result, all those who wish to transcend our existing economic, social, and political arrangements ought to oppose both the Democratic and the Republican parties, to work to expose what they really stand for and how, together, they manage the system that oppresses the vast majority of people in the country. Both parties are equally committed to and essential parts of contemporary American capitalism, the leader and linchpin of the global imperialist system.

But, of course, all this is silly. Just as there is no international revolutionary proletariat on the horizon today there is also no sign of a drive toward a spiritual revolution on the part of any significant section of the world’s population. We do see a striving for freedom in various countries in the world—in Ukraine, in Iran, in China—but the conception of freedom in the minds of the majority of people in these countries does not reach beyond bourgeois democracy. That is certainly better than what they currently have, but it is not the vision I hope and yearn for. That vision, at least for now, remains the delusion of a silly, and ultimately ridiculous, old man, one who continues to passionately believe in the dream of his youth.

Utopian Tendency Discussion

About 10 days ago, Ron posted a statement of his “current political view.” I found the statement provocative in the sense that it was a thoroughgoing rejection of many, many common assumptions of the left (including, in some respects, those of our own historic political tendency). At the same time, I think the statement was consistent with a rejection of Marxism (and its implications) and the embrace of a revolutionary libertarian anarchist point of view. To date, there has been no discussion of the statement, despite its prima facie controversial essence. This is an attempt to initiate such discussion and clarification.

1. Ron states that his political goal at the moment is to advance a “maximal libertarian vision of a free society.” I share the view that a tiny group of people who have (as close as is possible) no influence over day-to-day events in the political arena should have as its number-one priority the articulation of a maximal vision. Does this imply that one should not (if one wishes) be involved in/support day-to-day struggles? Not in my mind. However, it does suggest to me that the former should not be sacrificed for the latter. Thoughts?

2. Ron defines his goal as “the creation of a cooperative, egalitarian, and democratic—that is, a truly free, just, and self-managed—society on a global scale; no rich, no poor, no state, just people trying to live together democratically, fairly, and cooperatively.” I share this goal—and it is my hope that all people in this discussion group share it as well. Do we?

3. Ron states: “Such a society can be created only through a revolution, the destruction of the current economic system and the creation of a new, totally different, one…. As a corollary of this, such a revolution cannot be achieved by working through the existing political structures, a strategy that leaves our current socio-economic arrangements intact. This means the firm rejection of any support to (or participation in) either the Democratic or the Republican parties, or, in fact, to political parties of any kind.” I share the view that our current society, with its powerful and biased economic and political structures, cannot be reformed, piece-meal into a cooperative, egalitarian, and democratic society. Certainly, it cannot be reformed through its existing political channels and institutions. But what is the relationship between the leap in consciousness (Ron’s description is “…the more or less simultaneous decisions and actions of the overwhelming majority of people in the world”) and a revolution? Ron comments on what such a revolution should not be: violent, the imposition of the will of a minority or technical majority, the coercive actions of the state. He argues, and I agree, that absent a “virtual consensus among human beings in a relatively short period of time, any revolution that takes place will merely result in the re-establishment of our current form of society, or something worse.” But that said, what in this context is a revolution? Ron offers as examples or models the fundamentally majoritarian, largely non-violent movements/revolutions that overthrew Communism in Eastern Europe in 1989. This is a start, but I think further examination of what the nature might be of a revolution that is rooted in a sudden (or nearly so) transformational attitude shift would be useful. That said, an argument can be made that such discussion is fruitless, much like a discussion of what a post-capitalist (more accurately post-the-present-reality) society might look like is fruitless because what it will look like can only (must only) be determined by the people shaping it.

4. Ron states that “truly democratic, egalitarian, cooperative, and above all, caring societies…. would require the evolution of the human species to a higher moral and ethical level than it has attained so far.” This statement flies in the face of any theory or philosophical outlook (first and foremost, given its tremendous sway, Marxism) that locates the path to the society we envision in an alteration of property forms, or the impulsion of a given class toward a given end, or the falling rate of profit, or cyclical crises, or…. I think the notion that the path to our vision lies in the “evolution of the species to a higher moral and ethical level” is heretical. I also agree with it. Likewise, Ron’s statement that “a conception of a revolutionary libertarian transformation of society requires the firm rejection, and ultimately, the complete transcendence of the contemporary left” is also heretical. Surely, there are people in this discussion group, in particular those who have been part of our historic tendency, who have thoughts, questions, doubts or disagreements about this challenge to the core beliefs of Marxism, Leninism, Trotskyism and much of anarchism. I would love to see some discussion of these, if they exist.

Rod

Everyone,

Ron’s piece contains a number of ideas essential to any attempts at reconstructing a liberatory revolutionary project. A decided move away from the wreckage and theoretical/moral bankruptcy gripping the full range of tendencies constituting the international Left. In conjunction with a public post, hopefully, we can get it together to begin to discuss its propositions amongst ourselves. Failure to even hesitantly begin to do so only cements our irrelevance as a serious affinity, faction, tendency or mere discussion list/group.

Here is a reaction to just one aspect of what Ron has written:

To me it is self-evident that the spirit in which activity is conducted is the prime determinant of an anti-authoritarian thrust to forms of organization adopted. Experience demonstrates he authoritarian Communist mindset occurs with twists across the full range of Left projects. Strong aspects of authoritarianism and elitism are alive, well and dominant in the practices and strategies of not only overt Stalinists but among Trotskyist, Democratic Socialist and Anarchist formations as well. This applies to BLM/Critical Race Theory driven militants and currents as well. Any serious look at the history, connections and practices of the latter exposes their version of combative cultural Marxist (Marcusian) assumptions. The Gramscian idea of counter hegemony fused with Maoist notions of cultural revolution and a “Long March” through institutions (with a focus on the educational) informs their cancel culture practices and drive to reshape thought and language. We are not witnessing a proliferation of simple ‘anti- racist and anti-fascist’ groups, initiatives etc.

Looking at things from another angle no organizational form inherently militates against bureaucratic, reformist or other negative outcomes. The history of the soviet/worker council forms contains not only plentiful examples of failure to realize their stated goals but cases of these bodies’ employment in bureaucratic counter-revolution. What rules out a dictatorship of ‘revolutionary’ committees’ as well as a that of a Party?

Much of what attempts to pass as anarchism seems to impart magical libertarian qualities to either committee, counter union or informal ‘insurrectionary’ abstractions.

Does an organization with revolutionary intentions in its united front approach to other popular bodies/movements conduct its approach in a spirit of cooperation or in maneuver and biding time in a spirit of conquest, reformation and the imposition of ‘correct’ thinking? Outward forms guarantee nothing, and labels are just that labels.

I will continue posts on a number of Ron’s other important observations.

Mike

February 11

Mike, Ron, and All,

I very much appreciate Mike’s comments on Ron’s statement.

Mike states: “Ron’s piece contains a number of ideas essential to any attempts at reconstructing a liberatory revolutionary project.” Mike goes on to write: “In conjunction with a public post, hopefully, we can get it together to begin to discuss its propositions amongst ourselves. Failure to even hesitantly begin to do so only cements our irrelevance as a serious affinity, faction, tendency or mere discussion list/group.” I agree with both these comments. In my December 20 post, I wrote: “Surely, there are people in this discussion group, in particular those who have been part of our historic tendency, who have questions, doubts or disagreements about this challenge (Ron’s statement—RM) to the core beliefs of Marxism, Leninism, Trotskyism and much of anarchism. I would love to see some discussion of these, if they exist.” (Given the time that has gone by, I am reposting below my 12/20 comments in their entirety in the hopes that these, along with Mike’s recent post, will stimulate discussion.)

In a private conversation with Ron, I said that I thought his statement did not make sufficiently clear that the longer-range views he articulated did not reject in any way support for/participation in immediate struggles that advance people’s interests and organization, even partially. I added that I thought his comments regarding our support for Ukraine implied this; Ron confirmed that indeed he did support such immediate struggles, and also that he saw his Ukraine reference as an indication of this. While I would still like to see this stance made clearer if the statement (in whatever form) were to be voted on, I am glad to see that Mike has assumed such support and has gone on to address the character of such engagement. I share Mike’s view that authoritarian and elitist dynamics are present in the entire spectrum of the left, including anarchism. (At the risk of stating the obvious, these dynamics exists on the right as well, and, in fact, consistent with Ron’s statement, are prevalent in human society generally.) Mike’s statementthat “no organizational form inherently militates against bureaucratic, reformist or other negative outcomes” is both true and central to this discussion. Dialectics notwithstanding, aggressive, hierarchical, manipulative behavior as a strategic outlook (means) does not result in kind, egalitarian, democratic and loving behavior as an end. It does not do so any more than elite, hierarchical, centralized ‘vanguards’ transform themselves into democratic, bottom-up institutions of governance (cooperation), as Mike argues, or that powerful, centralized state abolish themselves ‘later’ as Ron has argued.

I recognize that it may be difficult to give up the view that there are certain ‘laws’ contained in history generally, and in capitalism specifically, that ‘impel’ certain categories of people toward taking certain actions that lead in certain directions, specifically the overthrow of certain ’forms’ and their replacement with ‘new forms.’ The view can make the seemingly impossible, seem possible. However, I believe that it is precisely this view, and it’s practical, theoretical and philosophical underpinnings, that has led, in its more radical forms, to monstrous societies, and in its less radical forms to a perpetuation of the fundamentals of traditional capitalism with ‘window dressing.’ These outcomes are not the result of mistakes, objective conditions or accidents of history—rather, the results flow directly from the underlying assumptions that guided them. Ron has articulated this in depth in his book, ‘The Tyranny of Theory—An Anarchist Critique of Marxism; I see Ron’s current statement as an extension of these views, moving beyond the boundaries of a critique of Marxism.

Rod

February 14

All,

Before proceeding to further remarks on Ron’s statement, I’d like to thank Rod for his comments. Given the list’s rather thin amount of discussion I would like to second Rod’s guess that folks probably have some objections or at least questions about some of the propositions Ron raises. It would be good to hear any such and without them how can we have an informative give and take.

As a tendency this list’s participants have shared over the long-haul varying degrees of anti-bureaucratic and increasingly anti-statist politics. Our evolving anti-elitist practices and vision has never spared the Left from critique and condemnation. I see no reason to soften or mute our criticism and adapt to one degree or another to the ” anti- rightist “essentially shared political perspectives and stances of the current Liberal/Left movement.

I find Ron’s piece to be a reaffirmation of the course we have maintained for years. It is a small but solid starting point for elaborating a viewpoint that remains revolutionary, anarchist and working class. How much can we leave of the approach that has animated us before we pass from the scene? It will undoubtedly be small but a series of real discussions and elaborations building on what Ron has written could leave a point/points of reference that are less so.

I fully identify with the statement’s open rejection of the 50% plus 1 approach to social struggle. This winner-take all attitude increasingly dominates the elite democratic contestation between the Democratic and Republican political classes. This attitude infuses the entire Left as well as the new ‘social’ formations, BLM etc. The spirit of direct action largely is practiced as a tool for imposing one group’s will upon the ‘unenlightened.’ Think of activists trained in this method/outlook gaining power in institutions or the state. These types have some significant sway in today’s movements. Concerns about the narrowness and sub-culture nature of an array of anti-racist, anti-fascist activist currents and outbreaks are sneered at, dismissed and often denounced by the sanctimonious and experientially impoverished. Language and thought are political. ‘Intersectionality,’ understood in the narrowest identarian-hierarchical sense renders activists crippled and close minded in terms of everyday popular shaping of demands and outreach. While there may be anger at the failings of leading liberal figures resulting in trashing and parodies of insurrection the masked militants cannot transcend liberalism. The liberals just don’t fight resolutely enough for them.

Usually when I raise these criticisms, I am told I am overstating the problem and perhaps succumbing to right wing propaganda. Yes, I follow right-wing developments and commentary closely. I likewise just as thoroughly follow developments on the left and “autonomous” trends as well. Furthermore, going back years I have been active in numerous projects with ensuing generations of activists and watched and have come to experience what I am critiquing firsthand.

I agree with Ron we need to stress the negative and authoritarian outcomes to revolutions of a violent character. I am not a pacifist nor is Ron (F-16s to Ukraine), but history underlines this fact and we should stress this and combat the flippant attitudes towards violence and the central role many of today’s and yesterday’s radicals and revolutionaries assign to it.

Furthermore, I am not a Democrat but an Anarchist (Avanti! Errico). While democratic forms and functioning have an important place in resistance movements, I hold to the idea of anarchy that arbitrary rule of majorities over minorities is not our operating principle.

Development through cooperation and dialogue is.

More to follow,

Mike

February 23

Everyone,

First, an apology for this belated contribution to what can be a very fruitful conversation. Ron brings up a number of perspectives that are worth wide discussion. I hope that others will add their views.

I’ll begin my contribution by stating that I’m in full agreement with Ron’s vision in paragraph 2, and in particular, his rejection of support to any political party. Also, I found enlightening the stance that freedom is a possibility—as opposed to an existing entity—in the universe; and as a corollary, at least to me, that people have a free choice (will?) to accept this possibility and the cooperative and caring attitudes that go with it.

This position is 180 degrees opposed to Marxism and any other deterministic or rationalistic ideology. These immediately pose the questions of: (1) who or what is to be the interpreter of the historical ‘Laws of Motion’ or rationality? Central committees? Planners? Or nowadays, non-profit foundations? (2) do the ends—‘socialism/communism’, or ‘rational planning’—justify the means to get there, which necessarily involve the suppression of individual thoughts and aspirations?

Second, I’m very much in agreement with the idea that a mass spiritual revolution must go hand-in-hand with a revolutionary overturn of capitalism and the state; again, as opposed both to Marxist determinism and a top-down planned ‘rational’ society. And that as advocates of this view, we need to look beyond the arena of the traditional left (narrowly, workers and oppressed people) to include small owners, farmers, artisans, and religious people.

Third, I agree with the complete rejection of Identity Politics. IP starts off by dividing people into different ‘identities’ (as opposed to, say, ‘human being’). While it may not have been the intention of those who began it, IP today is used by those in power to divide and conquer different ‘identities’ in the same way that the racial classification system was set up by the 17th century ruling class.

IP is reinforced by intersectionality. The rather obvious observation that people may be oppressed in different ways by different economic, political and cultural systems—intersectionality—has has been turned into a poison, glorified in academia, and used to divide people by defining hierarchies of oppressions.

Unfortunately, most of the current anarchist movement (or ‘scene’) supports the Democrats in one way or another. This is true even for those who are formally anti-electoral. Under the banner of ‘organizing’, building ‘assemblies’ or even ‘dual power’, they leave the political space open to parties whose aim is either to take the rough edges off the existing state or to build a new, even more authoritarian one.

For example, Black Rose, used to (and most likely still does) advocate ‘building power’, or ‘counter-power’, or even ‘dual power’ (as if dual power can be’ built’ by a collection of anarchists, not to mention its implicit acceptance of capitalism and the state). Flowing from this was a program of ‘organizing’ for a multitude of reformist proposals, or just plain ‘organizing’. The word ‘revolution’ seldom was mentioned except as a distant goal.

Anarcho-statism hasn’t been confined to Black Rose. Prior to its founding NEFAC (North-East Federation of Anarcho-Communists in the U.S. and eastern Canada) included a tendency called Barricada which, as the name would imply, admired statist Latin American revolutions. And after Barricada fell apart, the U.S.-based remainder took up the anarcho-social democratic practice later replicated in Black Rose. The Canadians really were no different politically, just more militant.

The black bloc folks repeat the tendency only with rocks, bottles, bear spray and occasionally, guns. As has been observed by others, they set themselves up as shock troops for the liberals.

While I agree that the best, truly liberatory revolution necessarily must be non-violent and requires a mass spiritual revolution, things likely won’t work out that way. A revolution may not have the vast majority of supporters but significant (and violent) opposition, and/or the needed spiritual revolution may not be as deep and wide as necessary. This brings up two questions: first, would it be just as well for this partial revolutionary scenario to fail? Second and similarly, what if a largely non-violent revolution in one area doesn’t spread quickly and is surrounded by hostile and violent forces? These are abstract issues now, but they present slippery slopes.

Finally, since there doesn’t seem to be even the remote possibility of a either a spiritual revolution of a minimally violent popular revolution at this time, it would appear our best hope is that for somewhere, somehow in the future younger folks will pick up and act on our tendency’s ideas.

Bill

P.S. Arianism is appealing.

February 24

Bill,

Thanks for your thoughtful comments on Identity Politics and also Black Rose’s reformist /non-revolutionary notions of building power/ dual power and its de facto capitulation to the Dems. Also, second your other lead in comments on aspects of Ron’s piece and its importance. Note the questions you raise in your next to last paragraph. Would appreciate posts of any questions/possible differences with Ron’s document from others on the list.

Mike

March 21

Thoughts on Revolution

By Wayne Price

Introduction

The following thoughts on anarchism and revolution are in response to a statement by Ron Tabor, ‘Thoughts on the Current Conjuncture’ (posted 02/07/2023). I was associated with him and his co-thinkers for many years, as he played a leading role in several far-left organizations. We met in the International Socialists (forerunner of the I.S.O. and of Solidarity) and associated in the split-off, Revolutionary Socialist League (RSL), followed by the Love and Rage Anarchist Federation, and finally by The Utopian; A Journal of Anarchism and Libertarian Socialism (now a virtual journal; many of those still around it regard themselves as the ‘Utopian Tendency’).

In the beginning, Ron saw himself as a revolutionary Marxist. Unlike most revolutionary Marxists of the sixties, he and his tendency interpreted Marx, Lenin, and Trotsky in the most libertarian, radically democratic, and humanistic possible fashion. We focused on Marx’s writings on the Paris Commune, Lenin’s State and Revolution, and Trotsky’s Transitional Program. By the end of the period, as mass movements died down, Ron and others of the RSL turned toward revolutionary anarchism. (Unusually, I had been an anarchist-pacifist before I became an unorthodox Trotskyist.)

Many radicals became demoralized by the political quiescence which followed the sixties and seventies. In his paper, Ron writes, “Today, the notion of transcending our current society—overthrowing it and replacing it with a more democratic and more just one—appears to have completely dropped out of political discourse. Even socialists and communists no longer talk about, let alone publicly advocate, revolution.”

A great many former leftists turned in a right-ward direction, many became liberals and others became neoconservatives. Former New Leftists came to admire the history of the Communist Party in the thirties and forties, when it was mostly reformist in practice. Others turned from the left altogether out of disgust with its totalitarian history and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Ron also turned toward the right, in his own eccentric way. Considering himself as a revolutionary and an anarchist, he came to reject “socialism” and ‘the left,’ claiming to be opposed to both the left and the right. (How this new general orientation changed his opinions on specific topics will not be covered here.) He disagreed with the classical anarchists, such as Bakunin, Kropotkin, and Malatesta. They had regarded themselves as ‘libertarian socialists’—or ‘anarchist-communists’—as opposed to the ‘state socialists’ or ‘authoritarian socialists.’ They saw themselves as the ‘left of the left.’

Ron came to reject all aspects of Marxism, even the most libertarian or humanistic aspects. (See Tabor 2013; also my review of that work, Price 2013.) While rejecting Marxism’s statist politics, many anarchists had valued parts of Marxism, such as its political economy—Bakunin has been called ‘the first of the anarcho-Marxists.’ (My own anarchism is still influenced by what I have learned from libertarian— ‘ultra-left’—Marxism and unorthodox-dissident Trotskyism. See Price 2022.)

In fact, a great many anarchists came to somewhat similar conclusions as Ron. For example, this is easily seen in the Comments sections of [link]anarchistnews.org. They reject ‘socialism;’ they denounce the left;’ they reject learning anything from Marxism (no matter how unorthodox). They generally are individualist-anarchists, Stirnerites, ‘post-leftists’ and ‘post-anarchists,’ nihilists, anti-civilizationists, and neo-primitivists. They are explicitly anti-working class and against the idea of revolution. Ron does not identify with these trends, but he has much in common with them.

Ron’s ‘Thoughts on the Current Conjecture’ covers a wide range of topics, such as free will and the existence of God. I agree with some of what it says, including rejecting a rigid determinism, opposition to the Democratic Party as well as the Republicans, and especially Ron’s support for the Ukrainian people’s war against Russian state aggression. Rather than go through all these subjects, I will only focus on Ron’s important discussion about revolution. In my opinion, it is a final abandonment of working-class revolutionary politics.

What Causes a Revolution?

“Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly, all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government….”

Thomas Jefferson, The U.S. Declaration of Independence

As Jefferson implied, revolutions are rare, but revolutions have happened. Sometimes they lost but sometimes they won—such as the U.S. Revolution. Some have expanded human freedom for a time, even if none has (yet) led to a fully “cooperative, egalitarian, and democratic – that is, a truly free, just, and self-managed – society on a global scale; no rich, no poor, no state, just people trying to live together democratically, fairly, and cooperatively,” in Ron’s words.

What makes a people or a class willing to stop suffering from “the forms to which they are accustomed,” in Jefferson’s phrase? The central factor is a change in their experience. Objective changes in society (caused ultimately by developments in the productive forces) shake up people, so that what they expect of the world and what they normally believe no longer seems tenable. They become open to new thoughts and experiences, new activities and directions—which interact with the objective changes. Minorities become ‘radicalized,’ looking for new ways of thinking—on the left or the right or some mishmash of the two. In turn they influence ever broader sections of society.

Ron Tabor has his own interpretation—or re-interpretation—of ‘revolution.’ Objective changes and new experiences have little to do with it. Yet he starts with a classical description. The good society “can be created only through a revolution, the destruction of the current socio-economic system and the creation of a new, totally different, one…. such a transformation cannot be achieved by working through the existing political structures, a strategy that leaves our current social and economic arrangements intact.” So far, so good, from the standpoint of revolutionary anti-authoritarian socialism.

But he rejects the goal of a different kind of society, one that is democratically cooperative, without a market or law of value. “The revolutionary conception I advocate does not mandate specific economic, social, or political institutions…. A community of small business people and other individual property-owners…might be either competitive or cooperative… It all depends on the attitude, the feelings, of the people involved.”